From the history of the prestigious prize to all the winners of 2021, here's your complete guide to the distinguished Nordic event

Each year, the Nobel Prizes - widely regarded as the most prestigious awards for intellectual achievement in the world - are awarded to individuals whose work has contributed to great progress in their respective fields.

Thanks to the brilliant minds of these impressive individuals, the advancements for which the prizes are awarded represent a hopeful nod to a better future ahead - and a positive note on which to bring the year to a close. We look at the people behind this year’s awards and at their unique contributions to the betterment of the world.

Malala Yousafzai received the Nobel Peace Prize Award in 2014. Photo: Getty

The history of the Nobel Prizes

In 1895, when the Swedish engineer, chemist and industrialist Alfred Nobel signed his last will and testament, he decided to leave the majority of his fortune to the establishment of a series of prizes in five categories: physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine, literature and peace. These are what have come to be known as the Nobel Prizes and, in 1968, Sweden’s central bank established an additional prize, the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. Since the prizes were first distributed in 1901, a total of 609 prizes have been handed out to 975 laureates who meet Mr Nobel’s own wish that the prizes be bestowed upon “those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” Some of the prizes have been shared by two either connected or unrelated winners, and even shared by the maximum allowance of three laureates, as is the case for two of this year’s prizes.

The Nobel Prizes are usually awarded to the laureates by the King of Sweden in an event in Stockholm’s City Hall, apart for the Nobel Peace Prize, which is given out in Oslo where, though the King of Norway is present, it is the Chairman of the Nobel Committee who hands over the prize to the laureate/s. These ceremonies always take place on Nobel Day, 10 December. This year, with respect to the pandemic, the Nobel Peace Prize laureates will receive their prizes at an award ceremony in Oslo City Hall, but the traditional larger scale events that usually accompany the other categories’ winners - and the subsequent banquet celebration - will not take place in Stockholm. Instead, the winners will receive their diplomas and medals in their home countries, alongside a virtual ceremony broadcast from Stockholm. Over the course of Nobel Week, from 6 to 11 December, a series of streams on nobelprize.org will present the laureates’ official lectures, the Nobel Prize Concert and the Nobel Prize Award Ceremonies for the following changemakers, whose work we celebrate in 2021.

Leymah Gbowee received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011 for her work in leading a women's peace movement that brought an end to the Second Liberian Civil War in 2003. Photo: Getty

The Nobel Prize in Physics

The most notable recipient of this prize is the one and only Albert Einstein, who was awarded the accolade exactly 100 years ago “for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect”. This year, the prize has been awarded to three people, “for groundbreaking contributions to our understanding of complex systems”: Syukuro Manabe of Princeton University in the U.S, Klaus Hasselmann of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany, and Giorgio Parisi of the Sapienza University in Italy. One half of the prize was jointly awarded to Manabe and Hasselmann “for the physical modelling of Earth’s climate, quantifying variability and reliably predicting global warming”, and the other half was given to Parisi ‘for the discovery of the interplay of disorder and fluctuations in physical systems from atomic to planetary scales”.

As the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted, this is the first time that the Physics prize has been awarded specifically to climate scientists. Their work is of particular importance as it shows the solid scientific foundations that are informing knowledge about climate change. Born in 1931 in Japan, Dr Manabe developed a computer model in 1967 that was able to confirm the crucial connection between the primary greenhouse gas carbon dioxide and increased warming of the atmosphere. He co-shares one half of the Nobel prize with Dr Hesselman, a German oceanographer and climate modeller who created a model that connected shorter-term climate activity, such as rain or weather actions, with longer-term climate activity, such as currents of the ocean and atmosphere.

Syukuro Manabe of Princeton University. Photo: Getty

Giorgio Parisi of the Sapienza University in Italy. Photo: Getty

Klaus Hasselmann of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Germany. Photo: Getty

To this, Dr. Parisi, an Italian theoretical physicist whose research has focused on quantum field theory, statistical mechanics and complex systems, is credited with discovering the interplay between fluctuations and disorder in physical systems - a way to help understand how climate change is due to the sum and interaction of many moving parts. The three scientists have been working for decades on their unique areas of expertise to understand the natural systems behind climate change, and their collective discoveries provide the basis from which predictions about the climate can factually be made.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Marie Curie was the first person to ever be awarded two Nobel Prizes: the Nobel Prize for Physics, in 1903, for her part in researching the radiation phenomena related to the discovery of spontaneous radioactivity; and the Nobel Prize for this category, Chemistry, in 1911, which she was awarded in recognition of “her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements radium and polonium”.

110 years later, the chemistry prize this year is shared by Dr Benjamin List and Dr David MacMillan “for the development of asymmetric organocatalysis”. Over two decades ago, Dr List and Dr MacMillan worked independently to discover a new chemical catalyst, creating a novel process for building molecules which has revolutionised pharmaceutical research. By allowing scientists to construct catalysts more efficiently and with considerably less waste and impact on the environment, it has allowed what the Nobel Committee has described as a “gold rush” of advancements.

Dr Benjamin List. Photo: Getty

Benjamin List is a German chemist and a director of the Max Planck Institute for Coal Research and Dr. MacMillan is a Scottish chemist and a professor at Princeton University in the US, where he also headed the department of chemistry from 2010 to 2015. Having received news of the Prize by text message, Dr Macmillan thought the announcement was a prank. So when Dr List contacted him to say he had received the same news, Macmillan bet him USD$1000 that it was not real and promptly went back to sleep. An expression of humility that has resulted in what is surely the only time there has been an unequal distribution of the prize’s financial component.

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is perhaps the most tangible field in which to grasp the human impact of advances made by the laureates. One such example is the work of the 1945 winners, Sir Alexander Fleming, Ernst Boris Chain and Sir Howard Walter Florey, “for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases.” The 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is equally progressive, and is awarded to David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian “for their discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch.”

Each day, as humans, we rely on our ability to sense heat, cold and touch. These sensations are vital for our survival, and shape our interaction with the world around us. While we may not need to think of how these sensations take place, this year’s laureates did - and identified the important missing links to explain the complex interplay of how our nerve impulses are launched so that we can feel temperature and pressure.

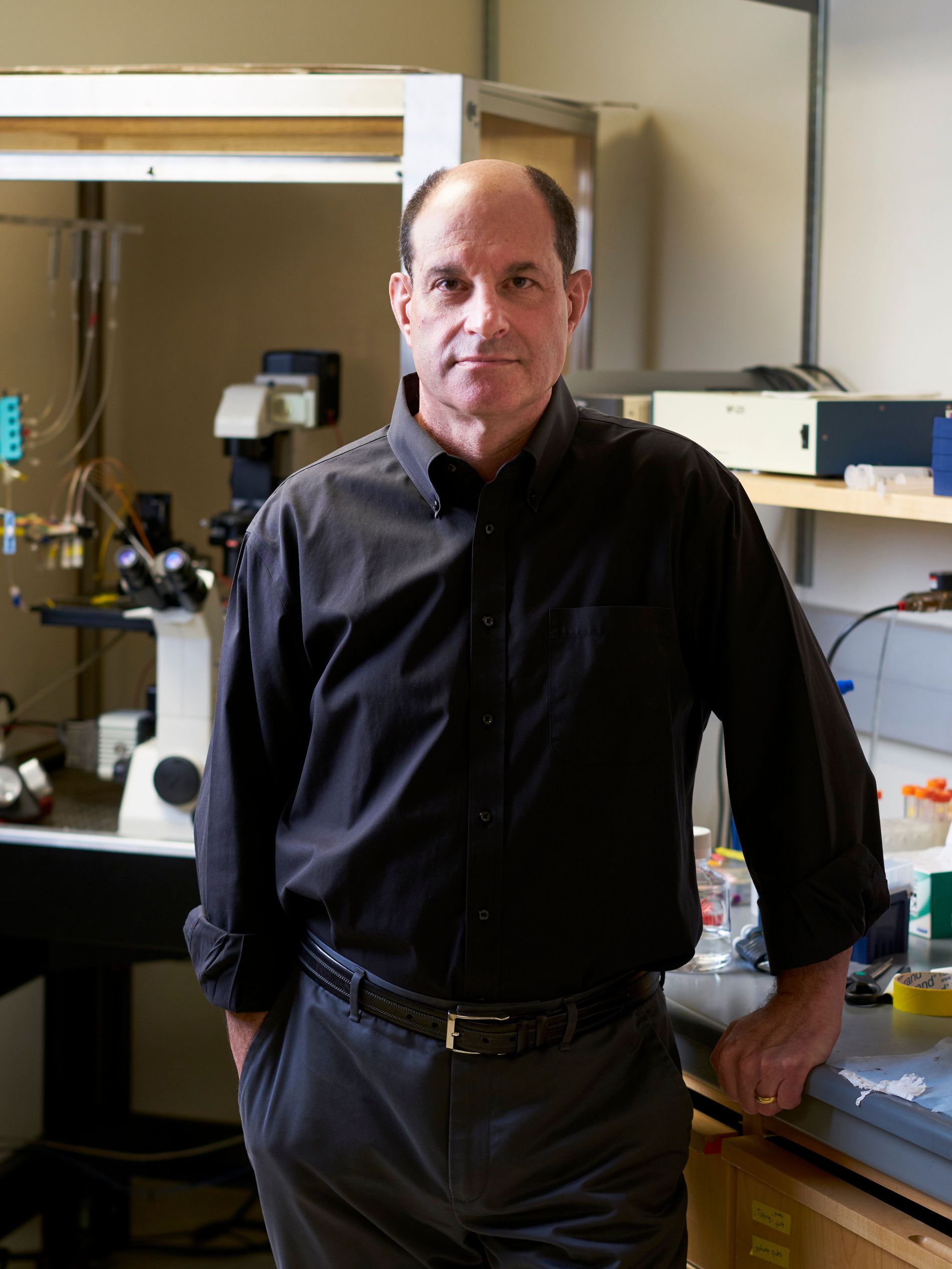

David Julius. Photo: Getty

Ardem Patapoutian. Photo: Getty

Patapoutian used pressure-sensitive cells to discover a specific set of sensors that respond to mechanical stimuli in the skin and internal organs. On the day the prize was announced, Patapoutian had his phone on “do not disturb” mode, and so had missed the Secretary of the Nobel Assembly and the Nobel Committee’s attempts to call him to inform him of his win. Instead, the Committee found a number on which to reach Patapoutian’s 92-year-old father, who in turn was the one to proudly break the news to the prize’s latest winner.

Julius’ work made use of capsaicin - the compound from chilli peppers that causes a burning sensation - to identify a sensor in our skin’s nerve endings that responds to heat. Of his discovery, he credits “looking at the natural world (...), how things that tickle our pain sensors work”.

Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel

This year’s three Laureates in Economic Sciences - David Card, Joshua Angrist and Guido Imbens - have shown that natural experiments can be used to answer central questions for society, and, through this approach to research, they have clarified precisely which cause and effect conclusions can be drawn. In a manner resembling clinical trials in medicine, they have used situations in which people are treated differently due to chance or policy changes, to answer big questions in social sciences.

All three laureates are affiliated with universities in the U.S, and David Card, of University of California at Berkeley, is a laureate this year “for his empirical contributions to labour economics.” Since his studies in the early 1990s, he has used natural experiments to challenge conventional wisdom and develop new analysis about the labour market effects of immigration, minimum wage and education.

Data from natural experiments is difficult to interpret, however, which is where the contributions by Joshua D. Angrist and Guido W. Imbens come in, which have garnered them praise “for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships”. Angrist, of Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Imbens, of Stanford University, solved the methodological problem in the 1990s, demonstrating how precise conclusions about cause and effect can be drawn from natural experiments - situations arising in real life that resemble randomised experiments.

As the chair of the Economic Sciences Prize Committee says of this year’s winners, the combination of “Card’s studies of core questions for society and Angrist and Imbens’ methodological contributions have shown that natural experiments are a rich source of knowledge.”

The Nobel Prize in Literature

In a category that boasts a list of past winners that reads like a literary who's who and includes stalwarts of the genre such as Ernest Hemingway (1954) and Pablo Neruda (1971), this year’s welcome addition to the list is the Tanzanian-born Abdulrazak Gurnah. 73-year old Gurnah is a novelist and Emeritus Professor of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent, where his main academic focus is postcolonial writing and discourses associated with colonialism, especially as they relate to Africa, the Caribbean and India. As a novelist, he is the author of highly-acclaimed novels such as By The Sea (2001), Desertion (2005) and the both Booker Prize and Whitbread Prize-shortlisted Paradise (1994).

As only the fourth black person to win the prize in its 120-year history, and the first black recipient of the prestigious award in almost three decades since Toni Morrison received the Literature Prize in 1993, Gurnah was chosen as the laureate of this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”.

Abdulrazak Gurnah. Photo: Getty

Born in 1948, he fled the Zanzibar revolution and escaped to Britain in the 1960s, and shortly thereafter began addressing his feelings of homesickness in his writing. These diaries started a long-lasting habit of using his writing as a tool to address and document his feelings of displacement and his experience of living in a foreign land as a refugee. Eventually, together with more fictional stories, his writings became his first novel, Memory of Departure (1987), which he wrote while also writing his Ph.D. dissertation.

This first book laid the blueprint for much of his subsequent body of work, in which he continues to explore the themes of exile, belonging and "the lingering trauma of colonialism, war and displacement". Many of his stories vocalise the experiences of the voiceless people living in the developing world, but who are relegated to existing on its outskirts due to governmental failures and humanitarian shortcomings. Though Gurnah’s first language is Swahili, he uses English as his literary language, and includes Swahili, Arabic and German into most of his writings, reflecting the melting pot culture of his Zanzibar roots and lending his literary language an authenticity and cultural nuance.

The Nobel Peace Prize

As Alfred Nobel himself once said, “Worry is the stomach’s worst poison.” And one of the most worrisome aspects of human existence is the absence of peace, which, fittingly, is the category of the last award - the Nobel Peace Prize. Recipients range from formidable individuals such as Nelson Mandela (1993), Malala Yousafzai (2014) and Barack Obama (2009) to organisations such as Doctors without Borders (1999) and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (2013).

The recipients of this year’s prize are Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov “for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace” and for their courage in fighting for freedom of expression in the Philippines and Russia respectively.

The Norwegian Nobel Committee states that; “Free, independent and fact-based journalism serves to protect against abuse of power, lies and war propaganda. We are convinced that freedom of expression and freedom of information help to ensure an informed public. These rights are crucial prerequisites for democracy and protect against war and conflict. The award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov is intended to underscore the importance of protecting and defending these fundamental rights.”

Dmitry Muratov. Photo: Getty

Maria Ressa. Photo: Getty

In her native country, the Philippines, journalist Maria Ressa co-founded Rappler in 2012, a digital investigative journalism media company that has seen her take on the role of defender of freedom of expression to expose growing authoritarianism and abuses of power, particularly that of the Duterte regime’s murderous anti-drug campaign and its related violence. Ms Ressa and Rappler have also tackled the prevalence of social media being used to spread fake news and threaten opponents in an attempt to influence the outcomes of public discourse.

In Russia, Dmitry Andreyevich Muratov has defended freedom of speech for decades, under increasingly challenging conditions. Part of the founding team of the independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, which launched in 1993, he has been the newspaper’s editor-in-chief for a total of 24 years, since 1995.

Being critical of power through a combination of fact-based journalism and professional integrity, the newspaper is a central source of censored information about aspects of Russian life that are often not covered by other media. It has published articles about the abuse of power by Russian military forces, corruption, police violence, unlawful detention, electoral fraud and “troll factories”, all articles to which opponents have responded with threats, violence and murder. Since the newspaper’s start, six of its journalists have been killed, a shocking fact in spite of which Muratov stands unshakeably by his beliefs that the newspaper must remain independent and that journalists must be free to write whatever they want.

At a time when the voices of so many fighters for democracy, justice and human rights are being silenced by governments, it is more important than ever to safeguard freedom of expression and commend those who are taking a stand to ensure that everyone - especially the voiceless - has a right to be heard. This year’s laureates represent all the journalists whose integrity and standards are being challenged in today’s world, where democracy and freedom of the press face increasingly adverse conditions.