An exhibition of works by one of Finland's most famous artists, Helene Schjerfbeck, will be presented at the prestigious Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), giving a Nordic art star a chance to shine

Long ensconced in the Olympus of Scandinavian art, Finnish painter Helene Schjerfbeck is finally going global. More than 100 years after her first solo show, in 1917 in Helsinki, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is presenting “Seeing Silence: The Paintings of Helene Schjerfbeck” (through April 5, 2026). The title, in suggesting something impossible, gets at the enigmatic nature of Schjerfbeck’s work, which, though suffused with a melancholic quietude, possesses an unexpected spirit of animation.

I first encountered the artist’s work at an exhibition in Stockholm, where I was struck by one of her self-portraits; Schjerfbeck depicts herself so unflinchingly. It is unclear in the painting whether she is resigned or defiant – possibly, she’s both. It would have taken some spunk to be successful as a female artist in her time, after all.

Schjerfbeck was born in 1862 in Helsinki. At four, she suffered a fall that resulted in a long convalescence, during which she entertained herself by making art with the supplies her father brought her. Considered a childhood prodigy, at 18 the Finn received the first of several grants that allowed her to study in Paris and travel in Europe and England.

Helene Schjerfbeck, Fête Juive (Sukkot), 1883. Oil on canvas, 45 1/4 × 67 11/16 in. Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Helsinki. Photo: Matias Uusikylä / Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation

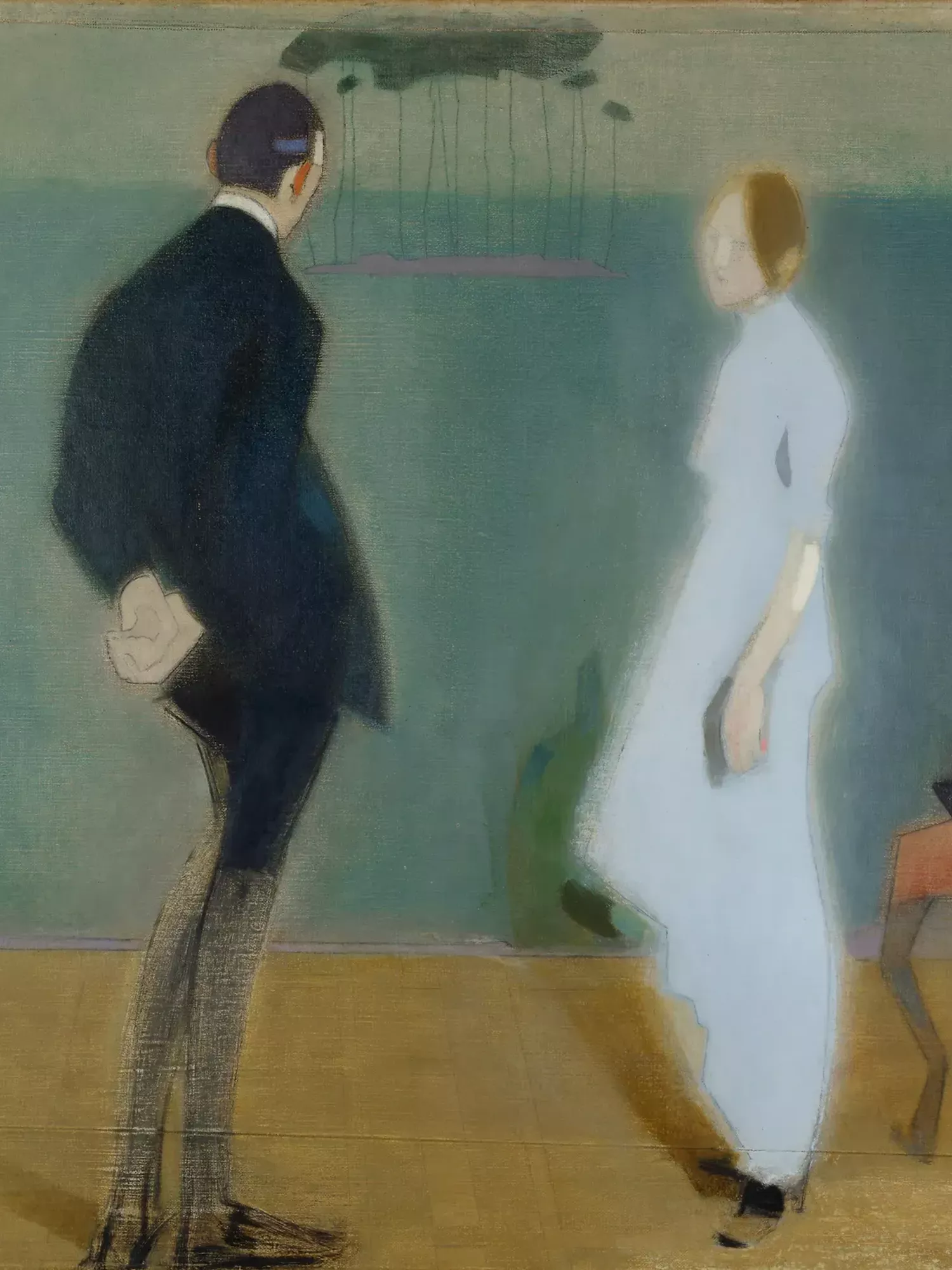

In 1880s Paris, naturalism and genre paintings were the preferred styles in the Salons where Schjerfbeck exhibited. The visitor to the Met sees how the artist, who was proficient in the vernacular of the time, went on to develop her own more abstract and interpretive style. Even when the subjects aren’t facing the viewer, as in The Seamstress (The Working Woman) (1905), Schjerfbeck’s scenes manage to feel at once spare and expressive, the composition and layers of colour speaking as loudly as the subject.

Finns are stereotypically reticent, and Schjerfbeck seems to honour that characterisation – partly in the service of allowing her viewer a say. “Let us avoid executing so precisely and exactly that our work closes the way instead of opening it,” she wrote to a friend. “Let us imply.”

Helene Schjerfbeck, Girls Reading, 1907. Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper. 26 3/8 × 31 1/8 in. Ateneum Art Museum, Finnish National Gallery, Helsinki . Photo: Finnish National Gallery / Hannu Aaltonen

Schjerfbeck lived a fairly reclusive life at the time. Returning to Finland in the 1890s, she lived in Helsinki before ill health and the needs of her elderly mother led her to take up residence in the small, rural town of Hyvinkää. Then, in 1923, she moved to the seaside town of Tammisaari.

Despite her geographical seclusion, the 20th century didn’t pass Schjerfbeck by. An avid student of art history, she made a series of paintings after El Greco – the Greek artist who often painted scenes of religious suffering – working from black-and-white reproductions. Schjerfbeck’s take on religious subjects had a lighter hand, exemplified by the resplendent Fragment (1904), painted after a trip to Italy to study Renaissance art. The subject is enhaloed with gold that remains luminous despite being worked over and scraped away. This painting, one of the most vulnerable in the exhibition, had special significance to the artist, who tried to locate it and buy it back after selling it.

Helene Schjerfbeck, Fragment, 1904. Oil on canvas, 12 3/8 x 13 3/8 in. Villa Gyllenberg / Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Helsinki . Photo: Matias Uusikylä / Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation

Madonnas were represented less frequently in Schjerfbeck’s work than modern women (herself included), whose up-to-dateness was communicated through gesture, makeup, and dress. It was a surprise to read that the artist, known for the gravitas of her work, was rather interested in fashion. As curator Dita Armory explained, Schjerfbeck “did read fashion magazines, and I know she used patterns acquired from Paris to make her own clothes.”

In 1944, at the suggestion of her gallerist, Schjerfbeck moved to Stockholm, where she painted her final self-portraits – some of which depict her mortality with an almost Goya-like intensity. She died at the Grand Hotel in 1946; 10 years later, she posthumously represented Finland at the Venice Biennale in the country’s first pavilion, designed by Alvar Aalto.

Schjerfbeck’s work is a discovery in terms of exposure – she’s little-known beyond the Nordics and in the ways her work relates, by coincidence, to the digital age. Where the artist faced the mirror seemingly without vanity, her interests as a portraitist lay not so much in representing who a subject was as interpreting a form. Amory writes that Schjerfbeck centred “light, space, volume not the soul of the sitter.” Some things, she seemed to determine, must be left sacred.

Helene Schjerfbeck, The Tapestry, 1914-1916. Oil on canvas, 35 1/4 × 36 1/4 in. Private Collection, Stockholm. Photo: Per Myrehed

Helene Schjerfbeck, Still Life with Blackening Apples, 1944. Oil on canvas, 14 3/16 × 19 11/16 in. Didrichsen Art Museum, Helsinki . Photo: Rauno Träskelin / Didrichsen Art Museum

Originally published on Vogue.com