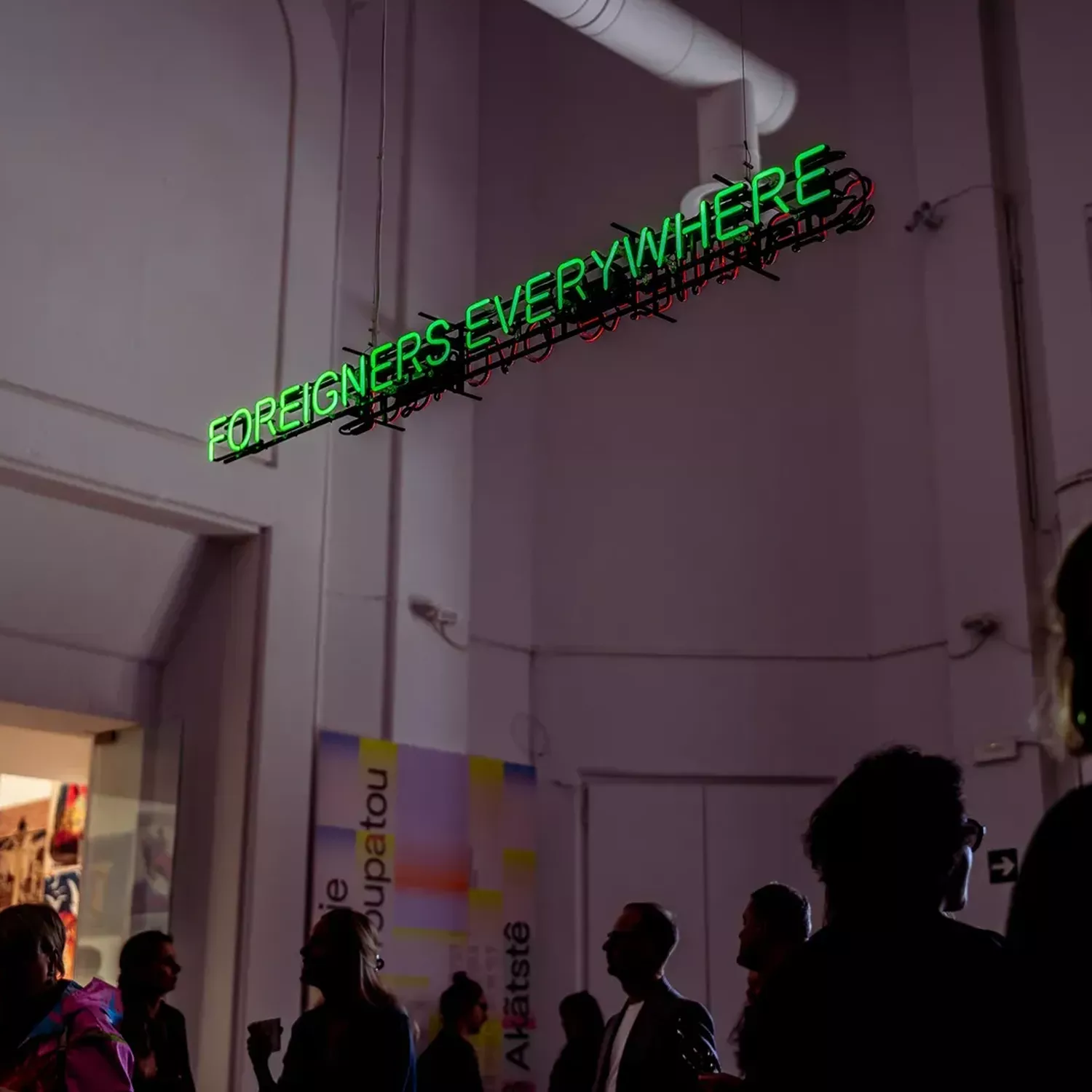

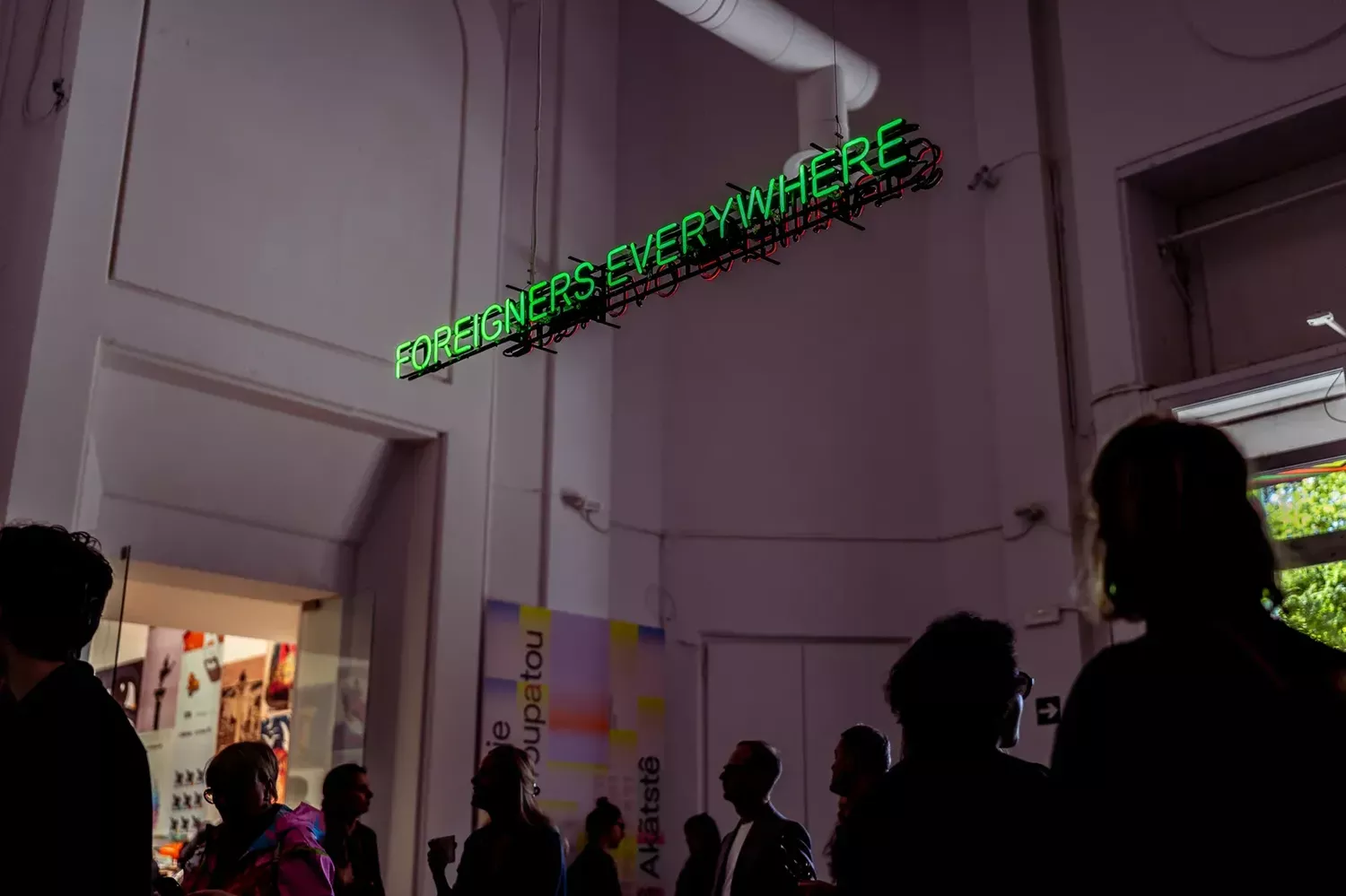

The 60th edition, themed 'Foreigners Everywhere' focuses on those – both artists and subjects – who are immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, exiled or refugees

The Venice Biennale opened last weekend for its 60th edition with the theme ‘Foreigners Everywhere’, inspired by the collective Claire Fontaine’s sculpture series displaying the phrase in neon characters in various languages for the past two decades. That premise, as laid out by curator Adriano Pedrosa (the first person from Latin America to lead the Biennale’s international art exhibition), has two meanings: (1) anywhere you go, you’ll encounter foreigners, and (2) everyone in some way is a foreigner no matter where they are.

Accordingly, this Biennale focuses on artists who are foreigners, immigrants, expatriates, diasporic, exiled or refugees. The Nucleo Contemporaneo section also highlights the queer artist, the outsider artist and the Indigenous artist, and the Nucleo Storico presentation centres modernism in 20th-century works from Latin America, Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

That all means there was a marked shift in what was shown this year compared to previous iterations, a clear and proud sign of support for artists in the margins. The international exhibition features 331 artists and collectives from some 80 countries, with the edge going to artists who have never participated; indeed, most artists mentioned below are showing at the Biennale for the first time, providing the longest-running international art exhibition an invigorating perspective.

Here are five standouts from the 2024 Venice Biennale.

Photo: Andrea Avezzu

Narrative strands

Having been beguiled by Pacita Abad’s just-opened exhibition at MoMA PS1, I was delighted to spy a cluster of her works toward the beginning of the Arsenale Corderie. The three large-scale quilted paintings from 1994 and 1995 – part of her Immigrant Experience series drawn from her travels, research, and own immigrant experience from the Philippines – are rendered in her signature trapunto style, which she helped to pioneer by stitching and stuffing painted canvases instead of stretching them over a frame. “Filipinas in Hong Kong” (1995), in which groups of Filipina migrant workers are dwarfed by skyscrapers and luxury stores, expresses Abad’s frustration at, then as now, the lack of political representation and government support for the large community of Filipina domestic workers who often face widespread discrimination and challenging working and living conditions.

Elsewhere in the textile-art vein, I was very taken by scenes on embroidered arpilleras created by unidentified Chilean artists during the Pinochet dictatorship; the Bordadoras de Isla Negra’s enormous, exuberant textile depicting a cross-section of Chile; and Claudia Alarcón’s works with Silät, a collective of hundreds of women weavers artists from the Wichí communities in Argentina, in which processed fibres of the native chaguar plant were woven into geometric textiles with surprising colour combinations evoking nature’s cycles.

“You Have to Blend In, Before You Stand Out” by Pacita Abad (1995) Photo: Marco Zorzanello. Photo: Courtesy of the Pacita Abad Art Estate

Outsider women in the spotlight

Self-taught artists Aloïse and Madge Gill are two names I learnt at the Central Pavilion and won’t soon forget. Aloïse’s works are spotlit in a room dominated by the captivating multipanel epic “Cloisonné de Théâtre” (1941–1951), which overflows with theatricality, sensuousness, florid colours and female figures in various states of undress. (Few self-taught female artists have achieved a level of fame comparable to Aloïse, who spent most of her life in a Swiss psychiatric hospital.) A similar overwhelming quality pervades Gill’s staggering 10-metre-long ink-on-calico drawing “Crucifixion of the Soul” (1936), a dense thicket of enigmatic, delicate women’s faces.

“L’Angleterre – Trône de Dehli” by Aloïse (1951–60) Photo: Matteo de Mayda . Photo: Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Indigenous artists shine

Works by Indigenous artists were among the most fascinating and memorable at the Biennale. Standouts include Marlene Gilson’s detailed depictions of Aboriginal communities and culture (Cate Blanchett sent a work from her collection to Venice); Joseca Mokahesi’s enthralling drawings of Yanomami spirits, myths, and shamanistic chants; Sénèque Obin’s absorbing portraits of Haitian culture; Abel Rodríguez’s vibrant and meticulously rendered Amazonian trees and rainforest scenes; and Rosa Elena Curruchich’s miniature-format paintings portraying daily life and customs (often highlighting the role of women) in her Maya Kaqchikel community.

“Building the Stockade at Eureka” by Marlene Gilson (2021) Photo: Marco Zorzanello . Photo: Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Cinematic parallels

As someone who often covers film, I was already inclined to gravitate to the Biennale’s offerings that were more aligned with cinema. But I was floored by Wael Shawky’s 45-minute film Drama 1882 in the Egyptian Pavilion. Directed, choreographed and composed by Shawky, the elaborate opera (filmed as a stage production) details the tumultuous events in Egypt that year as the nationalist Urabi revolution fought to cast off imperial influence. It’s sure to be one of the most powerful and mesmerising pieces of performance I'll see this year.

The adjacent Serbian Pavilion was similarly engrossing. Aleksandar Denić’s experience as a stage designer and film production designer is evident in “Exposition Coloniale”, which addresses the legacies of colonialism through an immersive set of rooms – a shop, bar, bedroom and sauna – imbued with an eerie familiarity but devoid of specifics. I also found the Swiss Pavilion compelling (not to mention funny, a rare thing on the Biennale grounds). Leaning back, you gaze up at a dome where Swiss Brazilian artist Guerreiro do Divino Amor’s video “The Miracle of Helvetia” depicts a culturally superior Switzerland, replete with typical stereotypes about Swiss clocks and cheese and touches of ’90s corporate kitsch and pop culture.

“Untitled #205” by Cindy Sherman (1989). Photo: Courtesy of the Skarstedt Collection

Chests, pushed forward

Away from the Biennale, boobs finally get the attention they deserve – serious artistic consideration, that is – at Breasts, a group exhibition celebrating them as icons and symbols. Curator Carolina Pasti has assembled 30 works from the 16th century to the present at ACP Palazzo Franchetti to explore how breasts have been understood and represented across cultures, encompassing themes of motherhood, illness, empowerment, sexuality and body image. The narrow entry corridor, swathed in red velvet, nearly smothers you in its warm embrace as breast lights lead the way to five rooms featuring bosom-centric works by Cindy Sherman, Salvador Dalí, Robert Mapplethorpe, Nobuyoshi Araki, Louise Bourgeois and many more.

Originally published on Vogue.com.