A century after its founding, Svenskt Tenn remains a beacon of enduring design and idealism. A new book from Phaidon captures the brand’s aesthetic brilliance and radical ethos – where beauty, ecology, and purpose go hand in hand

Last year, Svenskt Tenn, the storied Swedish interiors and design shop founded in 1924 by Estrid Ericson, marked 100 years in business. Carrying the celebratory spirit forward is a new book from Phaidon, Svenskt Tenn: Interiors, edited by Nina Stritzler-Levine, formerly of the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, which combines scholarship with upwards of 500 images.

As with Hedvig Hedqvist’s 2023 biography (in Swedish) of company founder Estrid Ericson, the 2024 'Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home' exhibition at Liljevalchs in Stockholm, and in keeping with the current interest in female creatives, the book’s opening chapters are devoted to Ericson. The designer and entrepreneur has sometimes been overshadowed by her friend and close collaborator Josef Frank, whose colorful, expressive prints have become synonymous with the brand. As Stritzler-Levine puts it, “Josef Frank is the name that has given Svenskt Tenn notoriety internationally. Estrid Ericson created many pewter items that are still in the Svenskt Tenn collection. However, her dual position as director/creative director was a more behind-the-scenes role despite the depth of its impact.” (Svenskt Tenn pewter and other items are incorporated into the design of some Toteme stores Frank’s philosophies and artwork are given due consideration in the book, which excitingly includes previously unpublished letters Frank wrote during the Second World War.

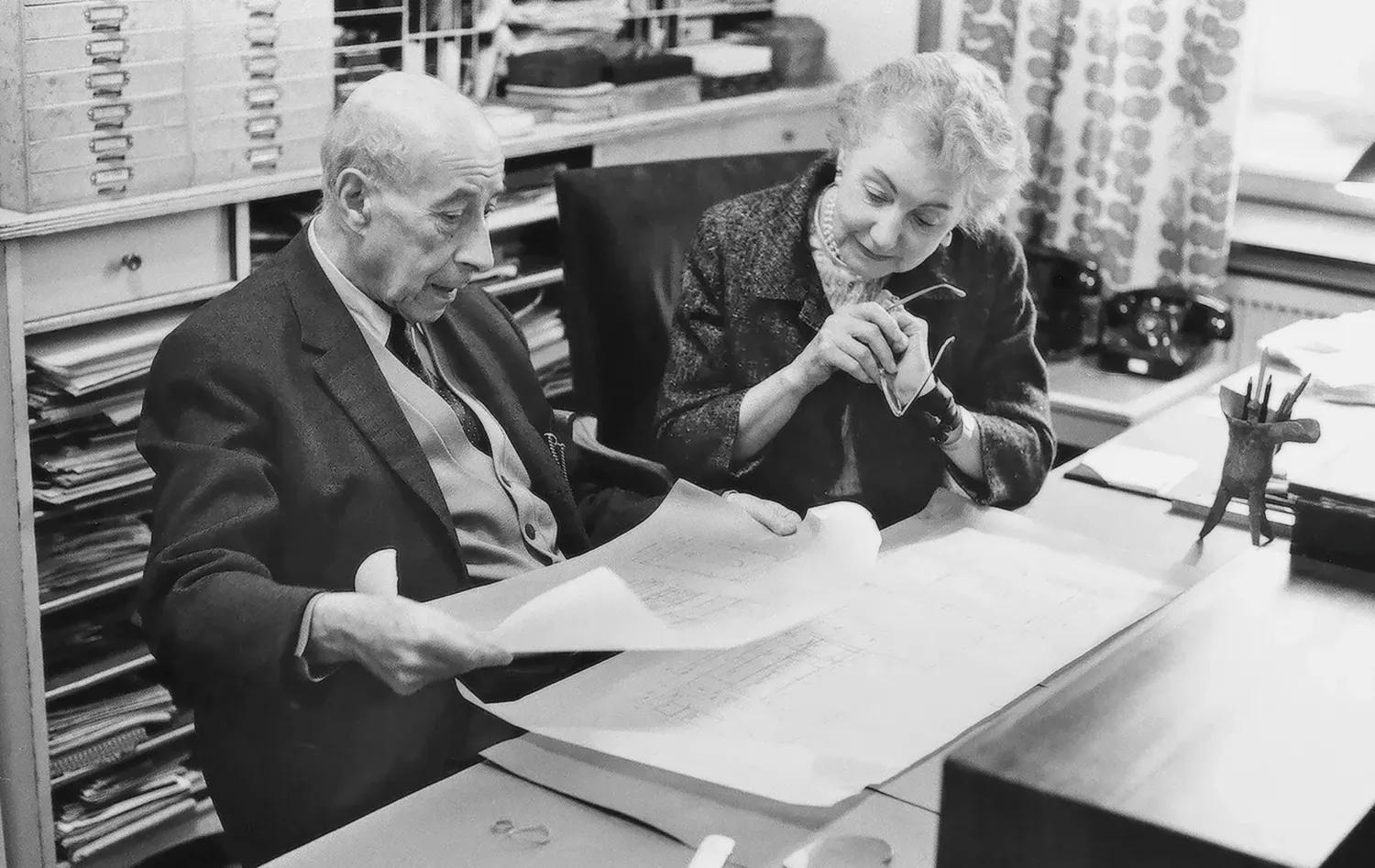

Josef Frank and Estrid Ericson in 1964. “The two artists formed a peculiar symbiosis. Ericson accepted everything Frank did, and he did everything she asked for.” —Eva von Zweigbergk, Dagens Nyheter. Photo: Lennart Nilsson / Courtesy of the Svenskt Tenn archive via Phaidon

Raised in Hjo, a small lakeside town on the west coast of Sweden, Ericson trained as a drawing teacher in Stockholm at what is now Konstfack, University of Arts, Craft and Design. At 30, with the inheritance left to her by her father, she established Svenskt Tenn (meaning Swedish tin or pewter). By the time House & Garden magazine dubbed Ericson “The Mistress of Modern” in 1939, the company and store offered much more than metalware, but the name stuck and has become synonymous with quality and discernment. As Ericson once said, “When I started Svenskt Tenn, I was a stranger in the world and quite impractical. Trusting the uncertain tomorrow of good taste.”

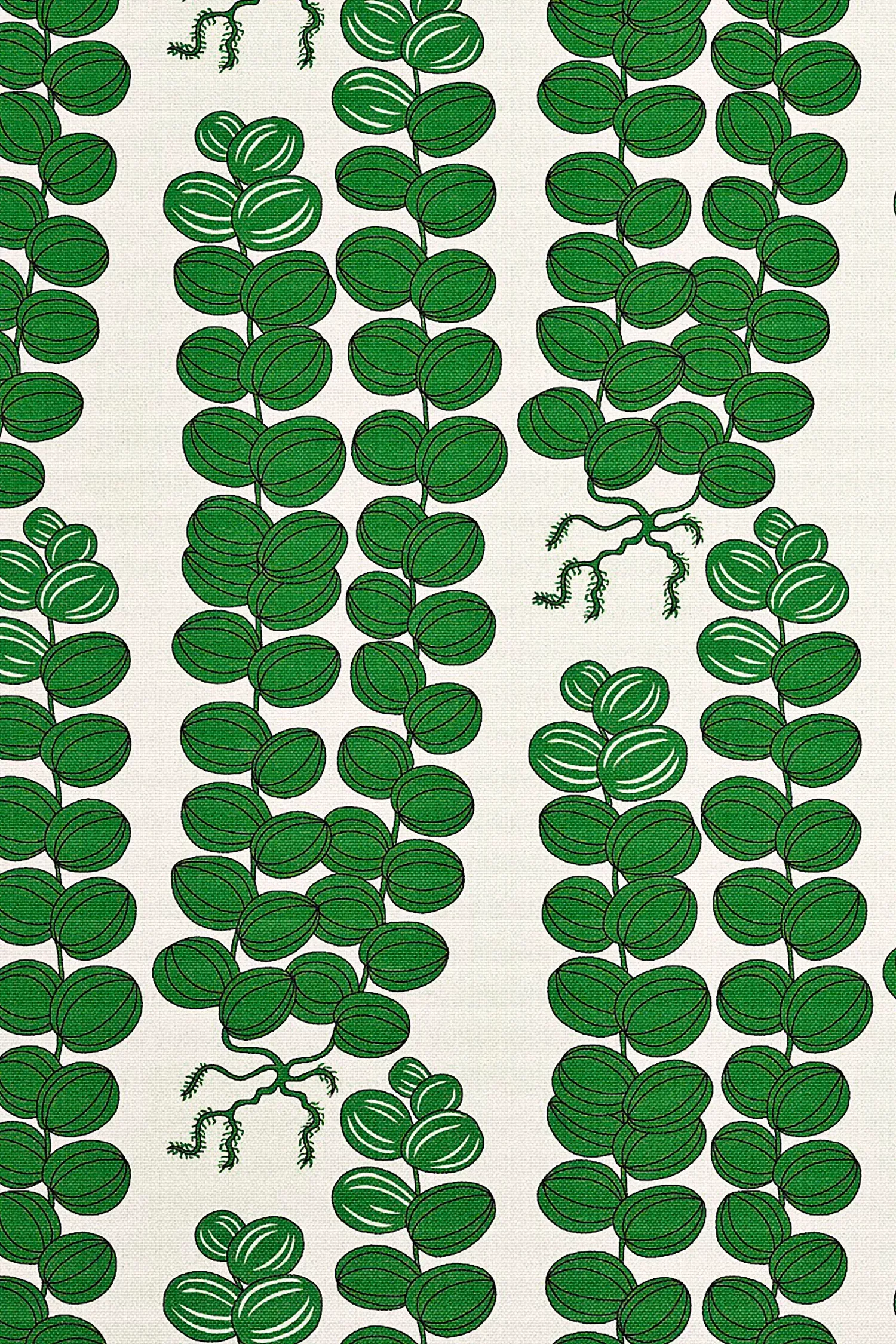

Celatocaulis, designed in Vienna, c. 1930. Photo: Courtesy of the Svenskt Tenn archive via Phaidon

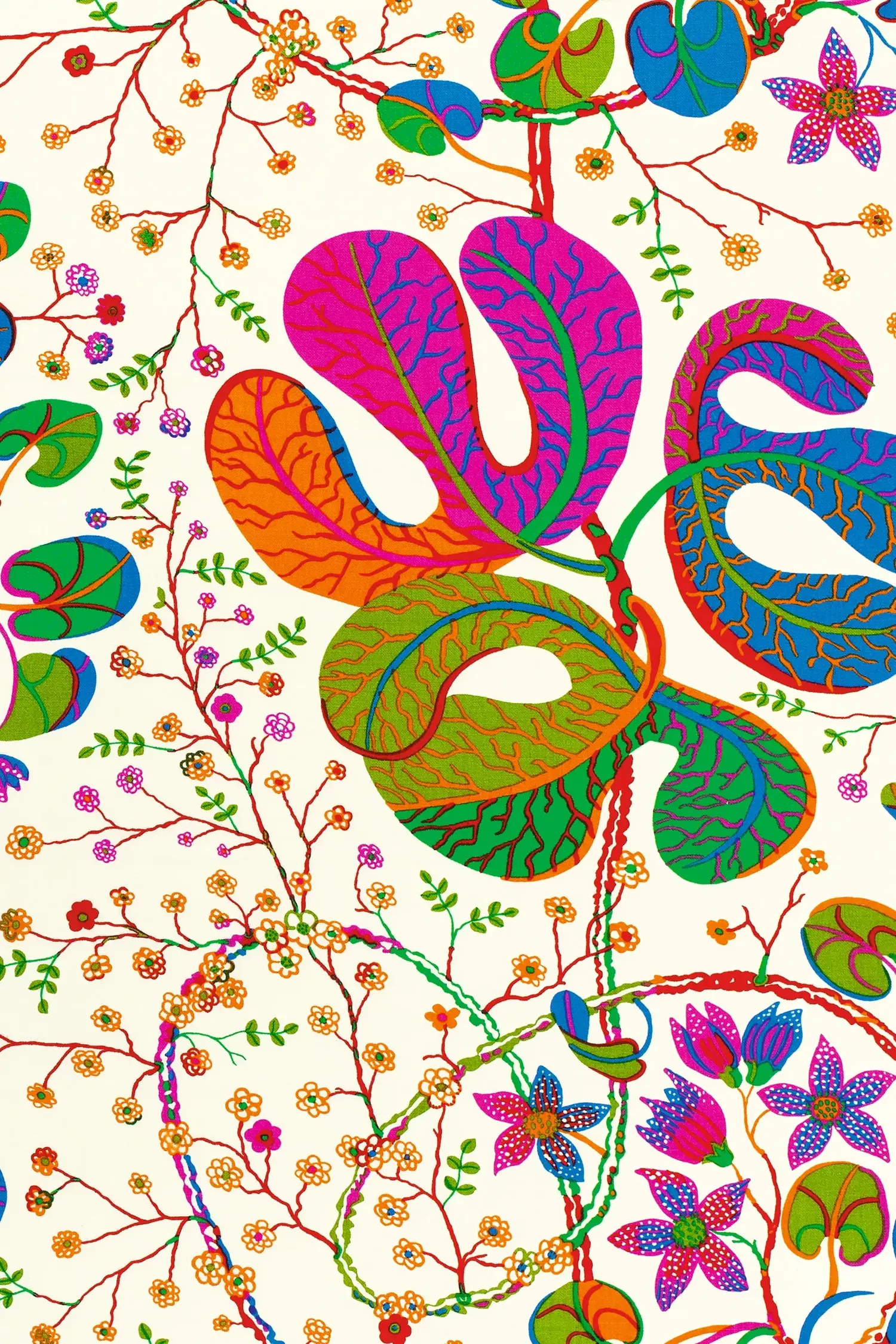

Tehran, designed 1943–5, first printed 1991. Photo: Courtesy of the Svenskt Tenn archive via Phaidon

Taste is, of course, subjective, and Ericson and her company grew and evolved with the times. The major shift in her lifetime was from Swedish Grace in the ’20s (with which Carl and Carin Larsson, Ericson favourites, were associated) to Functionalism in the ’30s. The former emphasised elegance, balance, the classic; the latter a more pragmatic, yet comely, practicality, often expressed through simplicity. Ericson herself was the fulcrum on which these tendencies balanced – with abundant curiosity, bonhomie, and a penchant for gesture, she brought a sense of home and warm hospitality to her work. As Hedqvist writes, Ericson “maintained that socialising around a beautifully set table was one of the best ways for people to be together.” A sense of stability was especially welcome at a time of great change that, the biographer noted, came with “a shift from an agrarian to a mechanistic society” as well as geopolitics.

“Estrid Ericson brought the world to Sweden through exhibitions and by importing items that evoked different cultures,” writes Nina Stritzler-Levine. “She took Sweden out into the world by participating in international exhibitions, beginning in 1925.” Estrid Ericson and Josef Frank, Living room installation in the autumn 1934 exhibition at Liljevalchs Konsthall, Stockholm. Photo: Courtesy Svenskt Tenn archive via Phaidon

Ericson set up home(s) at Five Strandvägen, close to the waterside and the Swedish Royal Opera. (The proprietress lived upstairs from the store.) The shop was arranged like an actual living space and Ericson filled it with flowers from her garden. As well as locally made pieces, she sold novelties discovered on her travels, and alongside exquisitely crafted and expensive items, there were more affordable classics like brass trivets and the clear glass acorn vase, which are still sold today. “According to the notes in her personal papers, Estrid Ericson believed that Svenskt Tenn’s success came from being ‘exclusive and eccentric,’” Hedqvist reports.

Svenskt Tenn has only one physical store, and a visit to the Stockholm flagship is like a pilgrimage to an ever evolving shrine of design. With new vignettes constantly being created in the store and regular collaborations, like those with Mamma Karin Andersson or Margherita Maccapani Missoni, the store is never the same twice. Making it even more welcoming was the recent addition of a ground floor cafe, where you can extend your visit.

When I started Svenskt Tenn, I was a stranger in the world and quite impractical. Trusting the uncertain tomorrow of good taste.

Estrid Ericson

The Phaidon book brings together imagery and more in-depth research. The archival assets are wonderful to see. Objects are isolated and photographed on a white ground; yet while this might emphasise the standing Svenskt Tenn in the pantheon of design, it captures none of the warmth or the gestural quality that is an integral part of the brand’s visual identity or offerings. Meanwhile, the text emphasises the humanistic aspects of the company, which – somewhat unusually – are built into the very foundations and structure of the brand.

Furniture from Josef Frank 1885–1985, Strandvägen Gallery at Svenskt Tenn, Stockholm, 1985. Photo: Svenskt Tenn archive via Phaidon

Living beautifully surrounded by objects of lasting quality is but one aspect of Svenskt Tenn – as a company concerned with the aesthetics of living well, it also explores how this can be accomplished through science and ecology. Since 1975, the company has been owned by the Kjell and Märta Beijer Foundation; in 2011, Maria Veerasamy became CEO, continuing the brand’s legacy of female leadership. All profits that don’t go back into the business are used to support scientific research and cultural projects. As Stritzler-Levine writes, “what makes Svenskt Tenn unique among other brands that support culture is its hybridity. It is a profit-making entity with a non-profit mission, a commercial entity that rejects obsolescence, the basic premise of consumption. Through its support for the Beijer Institute, Svenskt Tenn contributes to research dedicated to finding solutions to environmental degradation and together the Beijer Institute and Svenskt Tenn aim to inspire a younger generation of aspiring designers to make improving the environment a focus of their work... Svenskt Tenn is a model of how corporate profits and values can be used for the betterment of society and how history can inform a vision for how design can help to create a better future.”

Veerasamy has said that Ericson possessed a “sublime sensibility.” The context for that remark was aesthetic, but what this book makes clear is that the legacy of Svenskt Tenn is to open up the idea of home beyond four walls to include the world, with the understanding that we must treat the earth as our home as well. At a time when capitalism and the idea of endless growth are being called into question, the idea – realised by Svenskt Tenn and the Beijer Foundation – that a business can strive to positively impact peoples’ everyday lives in terms of aesthetics and well-being rather than being solely motivated by profit, sounds nothing short of revolutionary.

Originally published by Vogue.com.