As Jonathan Anderson makes his couture debut at Dior, we step inside his world – where pressure, process, and possibility collide

Portraits by Annie Leibovitz. Fashion Photographs by Stef Mitchell.

The light outside is pale and fading when, late one Friday afternoon, on a quiet street in Paris, Jonathan Anderson settles at a large table in his office to sift the pieces of the future. “What have we got to go through?” he asks.

With an air of surgical focus, his design director, Alberto Dalla Colletta, runs through the day’s couture decision points, then turns to urgencies in women’s ready-to-wear. “This is that skirt we repaired,” he says, riffling through a sheaf of papers. “It’s becoming more of a thing, which I thought was fun.”

“The back is nice,” Anderson says briskly, and then nods for the next item. Tall and relentless, with a flare of auburn hair and a tumbling Irish baritone of a voice, Anderson, at 41, is the new holder of one of the most powerful jobs in fashion: the creative directorship of Dior. When his appointment was announced last year, it was greeted, across the industry, with a shimmer of excitement. He was finishing 11 years at Loewe, during which he energised the field with a style of creative eclecticism that reached across fashion history and his own scattered interests to bring a crisp new allure to the market. And he did it, remarkably, while leading his own London-based brand, JW Anderson, which is now 18 years old. His couture debut, in February, was a springtime explosion of flowerlike volume that drew on the wide technical range of Dior's expertise.

“ He can just go in any kind of direction – I don’t think of his designs as looking like one thing,” says Jennifer Lawrence, among the first to wear Anderson’s Dior dresses on the red carpet. “Normally you get maybe three sketches that are all in the same universe. With Jonathan, it looks like 25 different designers sending me 25 different options. His range constantly amazes me.”

Dalla Colletta moves on to the next thing, vaguely apologetic. “The colours didn’t come out major, in my opinion. The brown is a bit–”

“Do you know what could be quite good, actually, is trying one where you have brown with gold,” Anderson offers, undeterred.

“Oh, whoa. Okay.”

“Could be weird,” Anderson says, and turns his head to one side.

On the mantel of a fireplace at the far end of the office is a bag emblazoned with the words “Ulysses by James Joyce”—part of the book-cover bag series that Anderson created—and his desk is set with a manual typewriter and candles in the shape of fruit. Eight wheeled panel boards, randomly arranged throughout the center of the room, are tacked with images of an advertising campaign in progress. A mannequin is hung with marked-up calico toile, and two clothing racks encircle the table. The excitement of Anderson’s appointment came, in part, from its high-wire stakes: He is the first designer at the house since Christian Dior himself to lead all fashion lines—women’s, men’s, and couture, including bags and shoes: 10 heavily freighted collections a year at what is now among the largest couture houses in Paris. Meetings are contrapuntal, and they move at breakneck pace.

“Then this was for the other reference you gave us,” Dalla Colletta says. “We’re going to try to do the jacquard by cutting all the fringes like that.”

Anderson yanks a hand through his hair and glares at the page. His working manner is generally that of a man outside the surgery of a village hospital, waiting for a doctor to appear with news. At his left elbow is, as usual, an outlay of personal effects, as if he has emptied a bag onto the table: an iPhone, a coffee cup, a bottle of Evian, a case with earbuds, a box of Tic Tacs, a box of cigarettes, a small tape measure, and a bright green zippered coin pouch that says 'Dumb as a Dream' – a Loewe collaboration with the artist Richard Hawkins.

“Nice,” he says at last, then peers more closely. “Though here the colors are not so nice.”

Dalla Colletta shows him two more pages, and then Anderson, heading to another meeting, races from the room.

“One-hour meetings in 10 minutes with Jonathan,” Dalla Colletta says with a smile, as he gathers up his papers to leave.

The pieces in Anderson’s debut women’s show paid tribute to the house’s history while toying with it and subverting it. Model Ajus Samuel in Dior (here and throughout; Dior boutiques). Fashion Editor: Alex Harrington. Photo: Stef Mitchell

“How do you find newness within something which is already old?” Anderson asks. “By having it dialogue with what’s happening today.” Model Betsy Gaghan in a dress from Anderson’s spring 2026 show. Fashion Editor: Alex Harrington. Photo: Stef Mitchell

Anderson’s first women’s show for Dior, held in the Tuileries, was for months the most anticipated in Paris. During the hour before it began, a throng spilled out from the park into the Place de la Concorde. Some bystanders wore costumes. Others lifted signs and screamed for every celebrity – Jennifer Lawrence, Sabrina Carpenter, Anya Taylor-Joy, Jisoo, Jimin, Robert Pattinson, Johnny Depp, and many others – who passed along a route marked by security guards through a parting in the crowd.

Within a huge, tan-colored structure built over the Tuileries’s octagonal fountain, the filmmaker Luca Guadagnino and his production designer Stefano Baisi had created a low-ceilinged gallery. The walls, mottled gray, were trimmed with layered Italian modernist moldings; boxy wooden stools were arranged as seating. “We wanted to create a space almost like a museum,” says Guadagnino, who met Anderson a decade and a half ago and collaborated with him on costuming for three of his recent movies.

When the lights dimmed to black, a short montage film by the documentarian Adam Curtis was projected onto triangular panes. “Do You Dare Enter the House of Dior?” read a title card, and the sequence that followed transfigured footage from Dior’s 78-year history into a horror film. Then the lights came up again, as if from an uneasy dream, and Anderson’s first women’s collection paraded out.

There were plissé twisted fabrics, curtailed skirt suits in tweed, and lace woven in eerie jagged patterns. There were variations on Dior’s famous bar jacket and playful subversions of its dress profiles. With its bib fronts, turndown collars, bow cravats, and rich, astringent plaids, the collection alluded to decorous midcentury ideas of fashion. But its strange volumes, vertically tightened proportions, and sudden, startling abridgments – as if whole forms had been made and then, like herbs, clipped to their living roots –gave the traditionalism an extreme and vaguely perverse edge.

Most noticeably, the looks echoed the vocabulary that Anderson introduced in his first men’s collection, in June, which included womenswear-inspired elements such as a high-volume, almost bustle-like pair of cargo shorts. The potential to design men’s and women’s collections not just side by side but in tandem, creating the new entity of a “Dior couple,” was the core of his pitch for such unusually comprehensive control, Delphine Arnault, the company’s chair and CEO, tells me.

“ It’s a modern vision: You can see the look on men and women with an interchangeability,” she says. It is also a vision that Anderson has pursued from his earliest days as a designer at his own brand, when, in 2013, he caused a stir by bringing into his men’s collection a pair of ruffle-bottom shorts with a miniskirt silhouette.

Justin Vivian Bond, the actor, cabaret artist, and trans rights advocate, describes Anderson as “one of the first designers to really bridge the gap between female and male collections – he’ll always have a guy or two in the women, and vice versa, and that speaks to me. I don’t feel it’s contrived: It’s logical and fun.” Bond first met Anderson more than 20 years ago, when Rufus Wainwright brought him to a show Bond was doing in London. “He made me a knit cap with feathers in it and a fake-ermine wrap and this amazing headband with nets that had flies caught in it – all very early Jonathan.”

Eventually, Anderson asked Bond whether they would perform in his senior show at the London College of Fashion; the two of them have collaborated on projects ever since, most recently on an opera called Complications in Sue. (Anderson designed the costumes.) “For all the seriousness and the intensity of his work, his sense of whimsy has never been lost,” Bond says, “which is part of what makes it so endlessly interesting—and allows him to keep evolving.”

One of Jonathan Anderson’s favourite words – the first he reaches for to convey praise – is radical. “Radical doesn’t have to be loud; radical can sometimes just be about the process of trying to work out what is new,” he tells me one day. “And what is new for Dior is different from what would be new for Loewe.”

Although Loewe is the oldest brand in the LVMH fashion portfolio, it had spent most of its history as a Spanish leather-goods company, making a name for its craft expertise with bags and moving into clothing tentatively. Anderson brought not merely energy, but, in a basic way, a public understanding of what Loewe style was. “Loewe needed a fashion language,” he says. “Dior does not need a fashion language! But it needs bag construction. It needs a world.” Anderson’s radical act comes in negotiating fresh juxtapositions, a new kind of relationship between this and that.

To evolve this way while holding on to what came before requires a certain relationship to the past. Few fashion shows begin with a horror reel; Anderson was trying to convey, playfully, the terrifying weight of taking on the helm of a historic Paris couture house, whose previous creative directors have extended from Christian Dior himself, who created the postwar New Look, to Yves Saint Laurent, John Galliano, and countless others: a menacing pantheon.

“I have never been under so much pressure,” he explains. “And it was not coming from myself, or from the brand. It was coming from the way everyone feels at the moment that fashion needs to be saved. I find that a strange utopia. I thought that the film was a way to put the audience into the position I am in.”

Justin Vivian Bond describes Anderson as “one of the first designers to really bridge the gap between female and male collections.” Model Charlie Jones in Dior. Fashion Editor: Alex Harrington. Photo: Stef Mitchell

For Anderson, most work is infused with struggle and drive. His father, Willie, was captain of the Irish national rugby team. (Guadagnino: “One of the iconic elements for Jonathan is the rugby sweatshirt – the way he goes with it through time and brands is beautiful.”) Anderson sees him as a figure of will. “My father comes from a dairy farm and decided very late, between 18 and 20, that he wanted to be a rugby player,” he says. “He played when rugby was not professionalized: If you won a match, you got a pound.” His brother, Thomas, is a rugby player too. “Watching my brother and my father’s relationship—the competitiveness – I always was like, Thank God I wasn’t into rugby!” he exclaims. And yet, growing up in Magherafelt, a small town in Northern Ireland, getting rejected from his first-choice fashion school, he assumed a similar psychic mantle.

“I’ve always operated in my life as an underdog, and if I’m not in the feeling of an underdog, I will construct an environment around myself so that I feel like I have to prove something,” says Anderson (who joked to me that he does not see a therapist because he works through his issues with journalists). The creative directorship of Dior is not a position that many people would consider an underdog post, but Anderson feels himself to be competing, at a disadvantage, with those who came before. “So many beloved designers have done it, and people will always love the designer of their period,” he says. “Someone like John Galliano was a genius in what he achieved at Dior: He broke the backbone. But this was a very different period.”

One of Anderson’s first jobs in fashion was as an assistant styling windows in the Prada store on Bond Street in London, under Manuela Pavesi. “I was just mesmerised by her – as a character, and by how she was using psychology in the process of selling a product in a window,” he says. “I remember one day, when Prada was doing robots, there was a window with a simple mannequin and a bag. I was like, ‘That’s interesting!’ She was like, ‘I don’t like it!’ And suddenly she was throwing product into the window – handbags, 50 robots. When I went outside, I was like, Oh. It was a saturation of product.” The eclecticism somehow cohered into an interesting whole. “She always had a meticulous contradiction of clothing – pyjamas with a crocodile coat,” he says. “I was petrified by her, but completely obsessed: How do you get that thinking?”

What makes me angry at the moment is that we have no patience. We just consume it, cancel it, move on from it. This is destructive of creativity.

Jonathan Anderson

Once Anderson succeeded on his own, he was recognised for a similar eclecticism, and also for being able to deliver a vision, through description and styling, that made the value of his work apparent to businesspeople, celebrities, and others who shape the market. “He presents very well,” Delphine Arnault says. Anderson points once more to his upbringing. “No matter how big, how famous, how rich someone is, there’s always an emotional way to see it from their side – that’s what I learned from my parents,” says Anderson, who reports that he still turns first to them for advice “on how to deal with people.”

Anderson is known for having chased his opportunities even more than he has been chased for them. At 20, while working for Prada, he got himself photographed for i-D magazine as a maker of brooches from found objects. He tells a story about how Delphine Arnault called him up out of the blue at around seven one morning, expressing interest in his work – “I remember trying to pretend that I was awake, which is always quite a feat, pretending your voice is awake and it has not been awake”—but Arnault remembers their first meeting a year earlier, at an exhibition in London. In 2013, the year LVMH invested in JW Anderson, he was asked whether he had suggestions for anyone to lead Loewe, which needed a creative director in a hurry. As the head of LVMH fashion at the time has recalled, Anderson suggested himself. By the early years of this decade, he was angling for a new assignment. “He started talking with me about what the future was, and what new projects we could give him in the group,” Arnault recalls. When Maria Grazia Chiuri, the previous creative director, stepped away from Dior (she’s now at Fendi), Anderson proposed that he lead menswear, womenswear, and couture all together.

By then, Anderson’s Loewe work had become a phenomenon. For his first seven years at the brand, he had focused on craft—a modern, elegant, and volume-based interpretation of a distinguished label’s savoir faire. Then, during the pandemic, he underwent a molting, shifting to a wilder, more playful, more openly eclectic conceptualism. This was the era of shimmering breastplates and digitally pixelated fabrics, of coats sprouting living grass, of Minnie Mouse pumps and balloon heels, of enormous strawberries inspired by a painting by William Sartorius. (For Uniqlo, with which he has an ongoing collaboration, he designed a collection inspired by Beatrix Potter.)

“ What he did with Loewe was groundbreaking. It was not just a brand shake-up; culturally it was a shake-up,” Lawrence recalls. “He was a really powerful artist who was taking in culture in a very specific, nuanced way.”

“I have never been under so much pressure,” says Anderson of his first runway show. Photo: Stef Mitchell

Anderson studies and collects a range of art, from the Flemish Masters to Anthea Hamilton; in London, he sits on the board of the Victoria and Albert Museum. For a while, he was interested in architecture, and he holds a lifelong passion for ceramics. The style that he began to cultivate in his collections after the pandemic – brighter and in a particular way more pared-down – seemed to afford him a new way to reference these interests head-on.

“That kind of incorporation of art and fashion is fundamental to Jonathan,” says Josh O’Connor, who began working with Loewe as a brand ambassador in 2017. “And I think that creating these incredible shows and then seeing people celebrate him gave him more and more confidence.” Anderson’s fascinations proved contagious: O’Connor, who had a ceramicist grandmother, came to share some. “I remember going over to Jonathan’s for dinner one night and seeing this incredible array – his ceramics collection is magic! He had Sara Flynn, an Irish ceramicist I’m a big admirer of. He had Lucie Rie. He had a big collection of Ian Godfrey,” he says. Anderson has attributed the birth of this passion to his maternal grandfather, who worked at a textile company, Samuel Lamont & Sons, in the Northern Irish county of Antrim. “He was the creative part of our family,” Anderson says. “And as a child, you were surrounded by a lot of forward-facing china.”

Many of Anderson’s friendships and relationships today have art at their centre. Lately, he has been dating the Catalan artist Pol Anglada, with whom he collaborated at JW Anderson. “In anyone’s private life, when you’re doing a job like this, it is hard,” he tells me. “I saw it with my parents when my father was working for the World Cup. When you go away and come back, you have to rediscover each other. As you get older, you learn you have to carve out the time if you want to protect it. Because it’s very easy to let go – you have to build in a mechanism.”

Otherwise, these days his interests often follow the arc of professional urgency. “At the moment, there’s a look book every week. There’s a campaign every week. You are mining for ideas most of the day,” he says. Then, as if thinking that this description failed to capture the thrill of it, he adds, “But it’s also an obsession – an artist or a person or a piece of vintage could inspire an entire collection.”

One December morning, I arrange to meet Anderson at the Musée d’Orsay, where he is stopping to visit a major exhibition on the work of the British painter Bridget Riley, whose 1988 canvas Daphne he owns. Anderson arrives late: He never looks at his daily schedule in advance, he says, or plans ahead for his next run of meetings, for fear he will second-guess whether they are worthwhile; unsurprisingly, he’s perpetually running behind. He seems tired.

“I’ve never looked forward to Christmas so much in my life – and I’m not a Christmas person,” he says, ticking off his current projects, for himself as much as me. “We’ve got one more fitting of couture, one more of men’s, and one more of women’s. And the launch of cruise, and then we just put the collection out to the market for pre-fall and Riviera. This season is always the hardest, because it’s so short.” He gives a grimace of a smile – “But still positive!”—and marches through the vaulted centre of the museum.

Anderson tells me he admires Riley paring down to the essence in her work. “Like, you have the confidence to go to the end,” he says. “In great Indian painting, you can find that. Even in a Rembrandt – they know when to stop. It invites your mind to think more about why you’re in front of it.”

The exhibition’s curator, Nicolas Gausserand, who has been following us, points out the colour of the wall: white. Riley, now in her mid-90s, insisted, against museum doctrine, that Seurat would be enhanced by white-wall display.

“It makes the whites whiter,” Anderson says, nodding. “It’s so radical.” He makes a last tour of the galleries, then charges for the door. “You need to go through briskly to start your brain,” he explains as we leave the museum. “If I go too long, I don’t see connections. I think because of my grandfather, it’s always been this idea of, How do you find newness within something which is already old? By having it dialogue with what’s happening today.”

We dip into a booth at the old wood-panelled riverside restaurant Le Voltaire for lunch – not our original plan, but we are running behind, so the itinerary has been, as is often the case with Anderson, reconfigured on the fly. Waiters bring plates of radishes, salamis, breads, and butter. Anderson orders a filet de boeuf, medium-well.

“Medium-well takes 30 minutes,” the waiter reports, in what might be artfully concealed dissension.

“Maybe just medium, actually,” Anderson says. “And some fries – go wild.”

“D’accord,” murmurs the waiter, with a poker-faced nod.

“You are mining for ideas most of the day,” says Anderson, photographed in the Dior atelier. “But it’s also an obsession – an artist or a person or a piece of vintage could inspire a whole collection.”. Photo: Annie Leibovitz

Anderson keeps one foot in London, where JW Anderson is in the process of expanding into furniture, art, and collectibles. He says he sometimes experiences cultural whiplash moving between there and Paris. “They’re very different cities in the way you eat or go out,” he says. “The funniest main difference is, I don’t know what it is in France, but they’re not very good at ice. The gin and tonics here are never very good, because the ice isn’t very good.”

As we settle into our meal, Anderson tells me that he takes his cultural project at the moment to be “trying to work out purpose” for a luxury brand in a digital age.

“The reason I was drawn to fashion was designing something for the future: You design it, you show it, and it goes into store in six months,” he says. “It means you give the consumer time to digest it. Now we are in this period where we are designing clothing to get stimulus for right now – when it goes in the store, it has lost its gas – it’s a sugar rush.” The trouble, he says, is that it’s almost impossible to propagate a standard of quality in that environment.

“It affects understanding. We’re used to consuming millions of images a day, but when it comes to reading, we consume less. We reply with an emoji. We voice-record, because it’s ‘more efficient.’ I would have thought, when I was younger, this would be the dream scenario.” (Anderson is dyslexic.) “But making clothing is brain-to-hand, and writing is brain-to-hand. They’re unusual actions.” It’s precisely that intentional effort that, for years, allowed fashion to exceed the sugar-rush present and get ahead to shape the future, Anderson thinks. The world needs time to sit with new ideas for them to take hold.

Anderson slices his steak vigorously. “My weakness is I can get emotionally strung out about the most mundane thing,” he allows. “It could be a model not being available, or it could be ‘We can’t get this one tiny venue.’ It could be a meeting that’s just not right. It forces me to go into anger – anger at myself, ultimately,” he says. “But what makes me angry most at the moment is that we have no patience. I don’t have any patience, so I’m part of the problem. We just consume it, cancel it, move on from it. I think this is destructive of creativity. I think there’s a lack of great film and a lack of great music because people are scared to be radical.”

Couture – a new realm for Anderson – fascinates him as a way to rebuild a culture of daring and appreciation. He has a dream of making Dior’s new couture more accessible – his model, he says, is an open-entry museum, like the V&A – so that people who cannot afford a couture dress can still learn to appreciate the work up close. “It’s about getting people to love fashion,” he says. “Couture may not be the thing that everyone buys, but it’s the trunk of the tree that supports the whole thing – the legacy, the hand, the knowledge.”

Two looks from Anderson’s Monday couture debut in Paris. . Photo: Acielle / StyleDuMonde

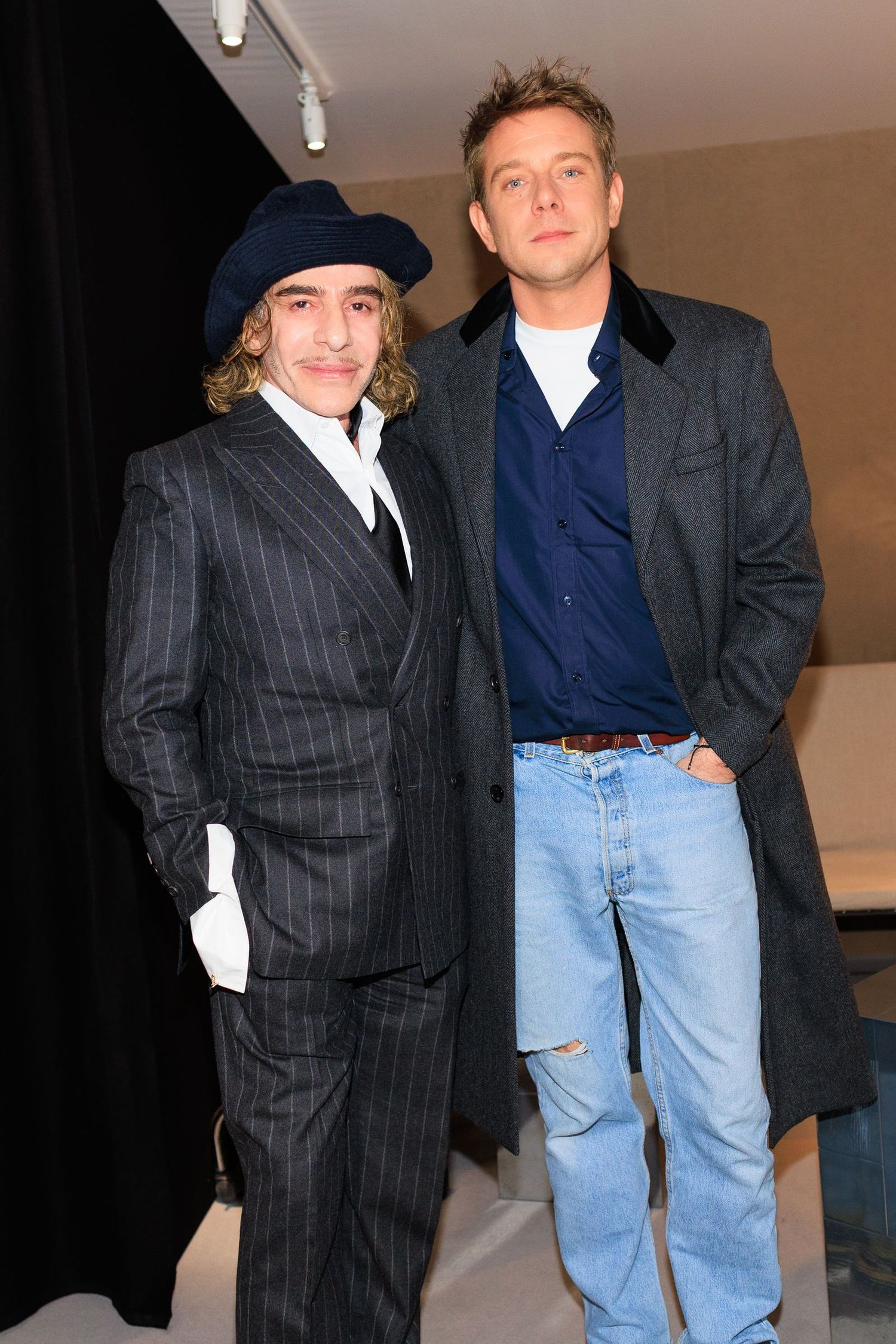

John Galliano – Anderson’s childhood hero – lent his support at the couture show. Photo: Acielle / StyleDuMonde

Image may contain Stephen Daldry John Galliano Blazer Clothing Coat Jacket Pants Formal Wear Suit and Jeans

John Galliano – Anderson’s childhood hero – lent his support at the couture show. Photographed by Acielle / StyleDuMonde

For Anderson, couture is also “the most personal” of his endeavours at Dior, because it is the form he is still learning. His debut couture collection was inspired by John Galliano, the first outsider to whom he showed his women’s collection – “because when I was younger, he was like God,” Anderson says. “John came with a bag of food from Tesco and these two immaculate posies of wild cyclamen – I love cyclamen.” The flowers, from Galliano’s own garden, touched Anderson deeply; in a tribute to Galliano – and an unusually gallant nod to a living precursor – cyclamen became a motif of the collection, from embroidery to decor, as Anderson worked from 18th-century textiles and antique portrait miniatures. He decided that the couture show would open with two versions of the lantern-shaped dress, black and white, that launched his women’s show.

“I love the technique, so I was like, Okay – how do we do it in a ready-to-wear way, and how can we show it in a couture way?” he says. “I collect Chelsea ceramics, and when you see first-period or second-period Chelsea, it will look the same, but it is manufactured in a completely different way. It’s not that one is better than the other; it is just that they have a different dynamic.”

The show, held in a softly mirrored space with a mossy ceiling of cyclamen, introduced a shimmering sweep of 63 pieces in spring and evening colours. In the language of couture, the plissé dress forms had a languid grace, the bead work came alive with individuated motion, and the petal forms composing the layers of some dresses seemed to bloom. The knitwear, in its unusual forms, had an air of organic growth that seemed to come from the garden, and the antique-inspired fabrics shimmered freshly in an indoor twenty-first-century light. Anderson sent delicate shell-like dress forms down the runway. He offered exquisite embroidery and black overcoats that were quiet masterworks of tailoring and drapery. He brought out great floral pompoms of earrings that seemed small bursts of joy. The show was, for its author as well as many others present, emotional – both Anderson and Galliano, who was there for the occasion, grew teary – and stood as testament at once to the beauty of craft precision and the large swell of change and continuity over time.

The balance between small distinctions and large endeavors is, in most cases, where Anderson’s creative mind and ambition meet. “As much as there are days when my head is about to blow, I always know that I will do everything in my power to make it work,” he says. “Not just for me, but for all the people I have brought into this project. I have to make it work – for them.”

In anyone’s private life, when you’re doing a job like this, it is hard. As you get older, you learn you have to carve out the time if you want to protect it.

Jonathan Anderson

Since Anderson took the Dior job, much of his life has been spent in transit. In November and December, apart from his normal commuting around Europe, he traveled to New York, Doha, and Beijing on errands for the brand, while working actively on six separate collections. One bright, crisp morning in Los Angeles, he tumbles down to the lobby of the Chateau Marmont to start a run of meetings which will culminate in the celebration of a new boutique in Beverly Hills. “I’ve always loved coming to LA – I would never live here, but I love being here,” he says, and begins devouring a large dish of yogurt and granola, gripping the spoon like a water dipper. Two young women across the room surreptitiously photograph him – a reminder, in the capital of celebrity, that with the ascent of Dior’s global profile, Anderson has become a celebrity himself.

On his first trip to Los Angeles, Anderson says, he got in a cab and told the driver to take him to 10086 Sunset Boulevard – Norma Desmond’s address. “It’s like a garage or something,” he told me. “But there’s nothing better than a Hollywood character of bygone days.” He partly laments the unmediated accessibility of today’s celebrities, which he thinks has eroded an iconographic power they once held.

“You had a moment where Dior would be creating the look for the studio for the actress, controlling the silhouette, the idea, the personality. I think you need that romance of what cinema told us fashion is.” He glances away thoughtfully, toward a candelabra near the bar. “I don’t mind Dior, in the future, becoming a little camp, a little bit performative – I think John opened the door to that. And Dior himself built the door.”

The new Dior boutique, a four-floor wonder with a floating spiral staircase on the prime block of Rodeo Drive, represents one sort of effort to restore a coherence of image. “It’s a new chapter for Dior,” Arnault says. The store, by the architect Peter Marino, includes a roof terrace, private lounges for VIP clients, and a restaurant with menus by Dominique Crenn, whose San Francisco flagship made her the first female chef in America to earn three Michelin stars. Since last summer, similar boutiques have opened or will open in Beijing, Milan, New York, and Osaka, all modelled on the enormous Dior store at 30 Avenue Montaigne in Paris. “These are very big statements and very big investments for us,” Arnault says; even in a digital age, in-person retail remains Dior’s sales driver. And Anderson’s comprehensive approach, taking control of all fashion collections together, suits the effort to build a unified—and universal – Dior world.

Anderson arrives at the top-floor terrace and lounge of the Beverly Hills boutique at twenty-five past seven. The guest list is, for a fashion dinner, eccentric and interesting. “It was the kind of gathering of individuals that really speaks to Jonathan and his mind,” Greta Lee, who attended in a simple, elegant gray Dior blouse and jeans, tells me. “It’s unexpected, often, these ideas and choices that he has, and the breadth and scope of what he cares about is genuinely interesting.” Lawrence comes with her husband, and Charlize Theron, a longtime Dior ambassador, arrives last. But there is also Gia Coppola; Maude Apatow; and Ejae, the KPop Demon Hunters voice star. Lauren Sánchez Bezos takes selfies and gives hugs. Mike White, the creator of The White Lotus, is there, apparently to his own surprise, dressed by Dior in a sweater and wandering around in fascinated alertness, as if taking mental notes. Many of the celebrity ambassadors whom Anderson has brought to Dior, such as Lee, are his longtime collaborators and carry a quirkier, wittier energy into what has long been a traditional French house.

Justin Vivian Bond describes Anderson as “one of the first designers to really bridge the gap between female and male collections.” Fashion Editor: Alex Harrington. Photo: Stef Mitchell

“Moments like this, for any artist, are particularly interesting,” says Greta Lee, “because they’re moments of transition.” Fashion Editor: Alex Harrington. Photo: Stef Mitchell

After shaking hands and greeting Delphine Arnault, who has also flown out for the occasion, Anderson rushes over to Lee and throws his arms around her. (“For me, she’s not a muse, she’s a friend,” he says. “It’s not just about wearing clothing; it’s, Can you have a drink and a three-course meal with that person?”) He is wearing a pale blue shirt, jeans, and brown moccasins. Waiters carry nori rolls filled with caviar, and tiny onion tarts resemble white folded cranes. On the patio, small cups are filled with Marlboro cigarettes. (When someone relayed to Arnault that this was not very LA, I am told, she joked that it was very LA – in the 1980s.) At ten after the hour, the guests are seated, and the dinner goes on, eventually acquiring a certain happy wildness. By a quarter past nine, Anderson is leading a troupe of celebrities to the terrace for a smoke. Half an hour later, he has shots of tequila sent around to everyone; more smoking follows.

“I think that moments like this, for any artist, are particularly interesting, because they’re moments of transition,” Lee tells me later. It thrilled her to watch Anderson move into a new realm. “The dinner was like that – a moment where things are really brewing.”

In Paris, as the holidays near, tourists teem before the twinkling lights of the Dior flagship, taking photographs. Half a block away – directly across the street from the Loewe shop – is Dior Heritage, the house’s meticulously kept archive of garments, accessories, perfumes, working notes, sketches, patterns, correspondence, and press clippings going back to its founding, all organised in pristine Dior-gray boxes. The documents have always remained in-house, but the archive has been engaged in a long, ongoing process of tracking down and acquiring the house’s early couture dresses. Perrine Scherrer, the archive director, shows me an early treasure: an intact Junon dress, often held to be Christian Dior’s greatest masterpiece.

When Anderson arrived at Dior, he made a broad study of this archive. “I did an exercise with the team where I wanted them to bring six looks of every designer who had ever been there,” he says. (His favourite Christian Dior piece is the ivory-coloured Cigale, from 1952: “It’s so aerodynamic – the construction of it is amazing.”) The next day, he visits a new exhibition at the Galerie Dior, the house’s 13-room public museum of its own history, half a block from the flagship store in the other direction. It opened in 2022, under one of Dior’s couture ateliers, and now 1,500 people visit each day, half a million a year, with tickets selling out a month in advance. The current exhibition is drawn from the collection of Azzedine Alaïa, who, for obscure reasons, hid the extent of his Dior collecting when he was alive, and the garments have never been shown. “The Alaïa Foundation has 600 pieces, and we selected a hundred to feature,” Olivier Flaviano, the gallery head, says.

Christian Dior presented his first collection in 1947 and died 10 years later, by which time his house was employing hundreds of people and doing business on five continents. Yves Saint Laurent succeeded him at the age of 21. “Now if a 21-year-old was sitting over a house of that scale, people would be horrified,” Anderson says. “You know what I mean? If we haven’t looked at the past, we forget the radicalness of it.”

Flaviano leads us through the exhibition: examples of Dior’s most successful early lines; an exacting recreation of the house’s original fitting room; the original in-house exhibition hall, where VIPs can still be received; a wall of magazine covers over the decades; and a photograph of Christian Dior’s office fortune teller and the charms he carried. “He was extremely superstitious, Monsieur Dior,” Flaviano says.

“Well, that’s one thing we have in common,” offers Anderson, before wandering off to take a call.

In the studio the next evening, Anderson sits staring at his boards, showing the upcoming advertising campaign.

“We’ve broken it into different kinds of characters – for me, the biggest thing is that Dior can be different men, different women, different people: The brand is big enough to not just have one monotype,” Anderson says. He never thinks about the campaign while designing, but it’s an essential part of his understanding of the work and how it might live in the world. In planning his first campaign, shot by David Sims, he considered what an “aristocrat” – the original audience for high fashion – might be in a post-aristocratic age.

“I’m really happy,” Anderson says with uncharacteristic openness, gazing at the boards. He points to a series of photographs of models Laura Kaiser, Saar Mansvelt Beck, and Sunday Rose crunched together on a love seat. “I just love this,” he says. “There’s a kind of happiness in it. When you go to a party, there’s always the one who’s genuinely having fun, the one who’s trying to have fun, and the one that’s seducing – a good depiction of what this can all be.” He turns to a board centred on Kylian Mbappé, the soccer player, dressed in jeans, a gray sweater, and a tie in an Eldredge knot. “Then you have this idea of leadership—you’re taking the footballer outside, transporting him. And then you have someone like Greta” – he turns to Lee’s board – “and you have these two pillars of how the girl can be, at this age demographic or that age demographic, and still have the same energy.”

He crosses his arms. “I will sit with this, and 20 other people will have an opinion about it, but I think it makes sense,” he pronounces, and allows himself a smile of relief. “I was so consumed by this idea of the anticipation and whether people are going to like it. But when I see all this, I feel very proud of the teams. I think it was the right direction. Is it the birth of a brand-new language? Not yet. But is it a step further from where I was in my previous job?” He looks at me with quiet delight. “It’s starting to go,” he says.

For Annie Leibovitz portraits: grooming, Jillian Halouska. Produced by AL Studio. Set Design: Mary Howard.

For Stef Mitchel fashion photographs: hair, Ryan Mitchell; makeup, Aurore Gibrien; manicurist, Magda S; tailor, Lauryn Trojan. Produced by NILM. Set Design: Giovanna Martial. Photo artwork by Martin Depalle.

Originally published by Vogue.com.