Giorgio Armani, the famed Italian designer, has died at the age of 91, confirms his eponymous brand

Giorgio Armani, who designed the uniform of aspiration that both defined the 1980s and shaped the course of fashion beyond it, has died, it was announced today. He had turned 91 on July 11. His passing was confirmed by the company.

“With infinite sorrow, the Armani Group announces the passing of its creator, founder, and tireless driving force: Giorgio Armani,” a statement read. “Il Signor Armani, as he was always respectfully and admiringly called by employees and collaborators, passed away peacefully, surrounded by his loved ones. Indefatigable to the end, he worked until his final days, dedicating himself to the company, the collections, and the many ongoing and future projects.”

Unarguably the most successful Italian fashion designer in history, Armani was also its most successful entrepreneur. He was the sole shareholder in his eponymous company, Giorgio Armani S.p.a, whose interests expanded far beyond apparel to encompass hotels, homewares, and even confectionery. The business he began from scratch in 1975, funded with the sale of his Volkswagen Beetle, saw revenues of 2.1 billion euros in 2019 and employs around 8,000 people worldwide. His own personal wealth has been estimated at 11 billion dollars. Remarkably, when he founded his company, Armani was already 40 years old. It would take him only seven years to go from unknown to Time Magazine cover star, which in 1982 represented the apex of cultural recognition.

Armani began designing both womenswear and menswear as a freelancer in the early 1970s, after a six year stint as protege to the tailor Nino Cerruti, for whom he worked on a sportswear label named Hitman. Prior to that he spent seven years working at the Milan department store La Rinascente, where he had served as window dresser and assistant buyer. Armani opened his own design studio with the encouragement of his partner in both life and business, the architect Sergio Galeotti. As Armani told GQ in 2015: “Sergio made me believe in myself. He made me see the bigger world.” The two men set up their company—Galeotti was chairman and co-owner—alongside assistant Irene Pantene (who still works for the company today) and showed their first womenswear collection on the Camera Della Moda calendar for Fall 1976, a collection for which they secured a distribution deal with Barneys.

At that first on-schedule show, Armani presented 12 models wearing looks featuring the light and loose deconstructed men’s suit jackets that he had already shown alongside menswear at a 60 look co-ed show in January. At the end, those 12 models came together down the runway, paused, and then danced to music played via record by Galeotti from backstage. Armani had already become a buzzed-about designer in Milan nascent’s fashion scene thanks to his supple and sporty leather blouson jackets for men, and these earliest collections for women proved similarly arresting to the media.

Shaun Casey wears a tweed blazer, Shetland vest, bias-wrap skirt, and shirt by Giorgio Armani. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, August 1977

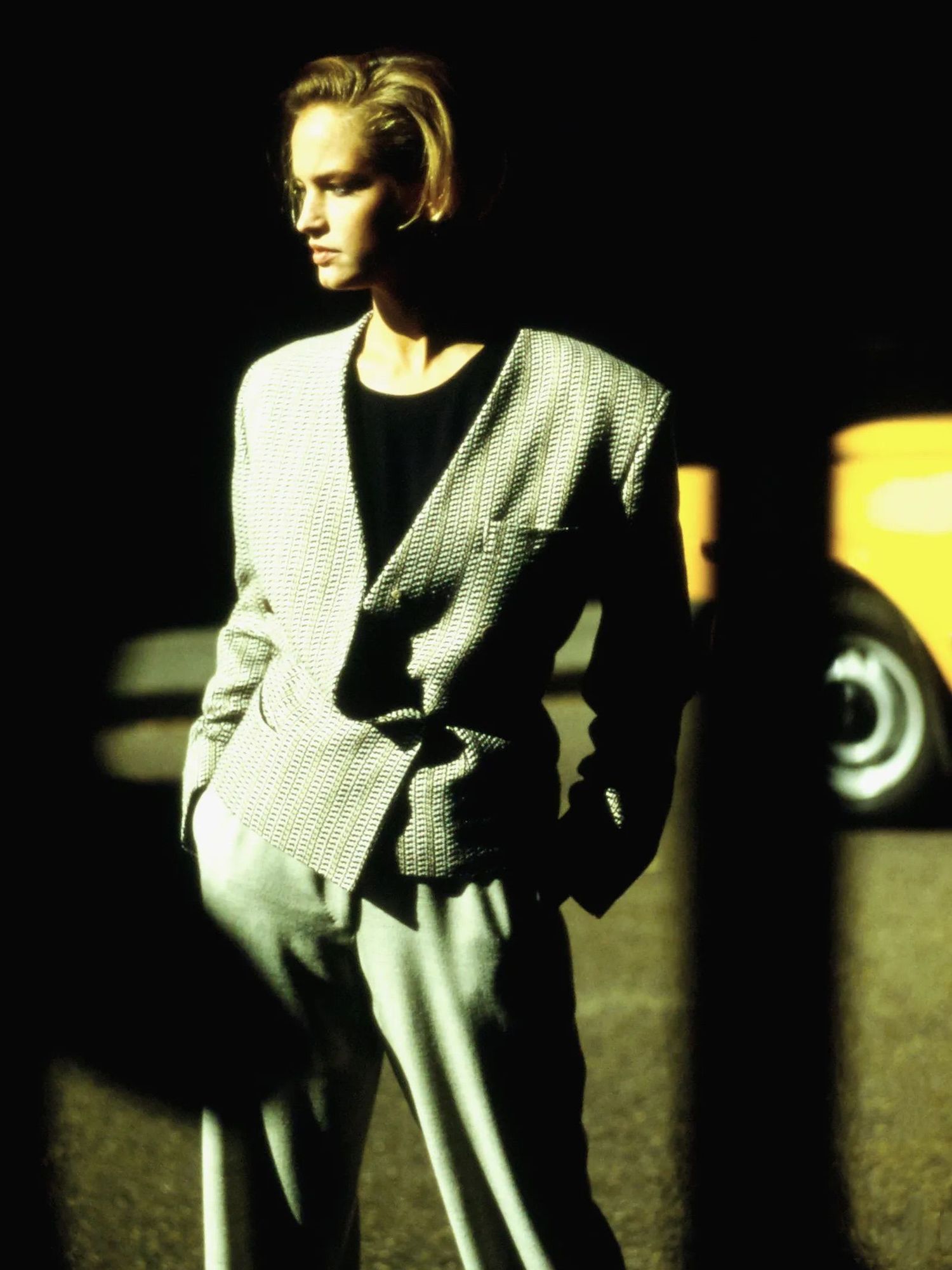

Bonnie Berman wears Armani's relaxed suiting. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, January 1984

Word of his prowess spread Stateside, where in April 1978 Armani received the first of three priceless pieces of exposure when Diane Keaton wore one of these jackets to accept the Best Actress Award at that year’s Academy Awards. This was followed by the coup that has lived largest in Armani mystique, his clothes’ starring role on Richard Gere in American Gigolo, a movie that was released in February 1980, and, as Armani told The Economist’s 1843 magazine in 2017: “was a sensation: everybody wanted to know what Gere looked so great wearing. So it gave me a sudden positive notoriety.” This stroke of luck was thanks to the recommendation of the manager of John Travolta, who had been originally cast in the role—when he dropped out director Paul Schrader installed Gere, and kept the Armani uniform.

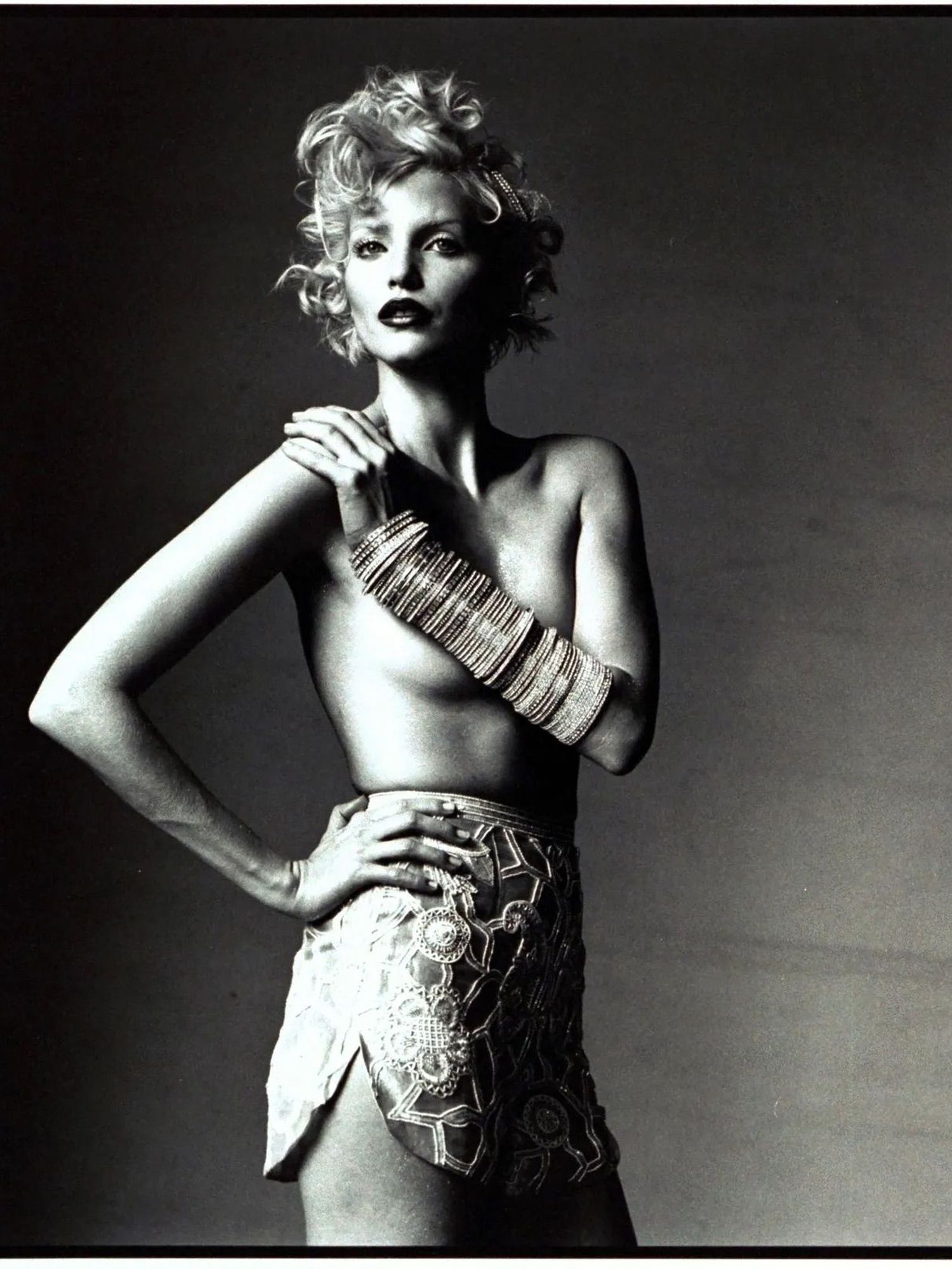

Photo: Peter Lindbergh, Vogue, September 1989

As the US was entering one of its peak moments of power and confidence, Giorgio Armani was on hand to offer an exotically organic and sophisticated expression of soft-toned, loose shouldered chic. His newly opened labels Emporio Armani and Armani Jeans offered a piece of the Armani action at a more attainable price. More than any of his peers in Milan—only Gianni Versace came close to matching the levels of exposure—Armani was quickly becoming a synonym for Italian fashion in the American and broader consciousness. “So many things happened so fast for me back then,” said Armani in 2017. “It was the time where everything was moving in my career.” Grace Jones wore Armani on the cover of her 1981 Nightclubbing album, from a Japanese inspired collection. Then came the Time magazine cover, and in 1984 the first episodes of the Armani-heavy peak ’80s TV show, Miami Vice, which would run for four years.

In 1985, however, personal tragedy punctured the seemingly constant upturn of Armani’s professional fortune. Following an illness—sometimes reported as heart disease, sometimes not—Sergio Galeotti died. “We lived without even saying a word about his illness, without even letting it weigh,” Armani told New York Magazine 11 years later. “He never saw me cry. He himself never said anything. In a whole year, he said once, ‘Giorgio, look how thin I have become’—that’s all.”

Bereavement hit Armani powerfully, but his business continued to grow. In Gabriella Forte, who had helped broker the Barneys New York deal in 1976 and worked for Armani from 1979 to develop the US market, he found a righthand woman with great drive who from 1985 often even spoke for him. Other key hires included the PR Noona Smith-Peterson, who spent eight years in the company, “special events coordinator” Lee Radziwill, and the Missouri reporter turned Armani ambassador to Los Angeles, Wanda McDaniel, who was hired by Forte in 1987.

Photo: Peter Lindbergh, Vogue, December 1987

While it is the 1980s in which the mould of Armani was defined, he continued to lead the direction of fashion into the following decade, particularly in menswear. For spring 1990 he proposed a three-button, higher lapeled and narrow shouldered but still softly tailored version of the sack suit which he named “The Natural,” and which would go on to define the dominant tailoring shape of the following years. Even the arrival on the scene of Prada and Calvin Klein could not dent its ubiquity. The same year as The Natural saw the release of Made in Milan, a Martin Scorsese edited documentary that shows Armani at work, and in which he observed: “Society changes and I change with it. I try to filter my ideas through a daily reality.”

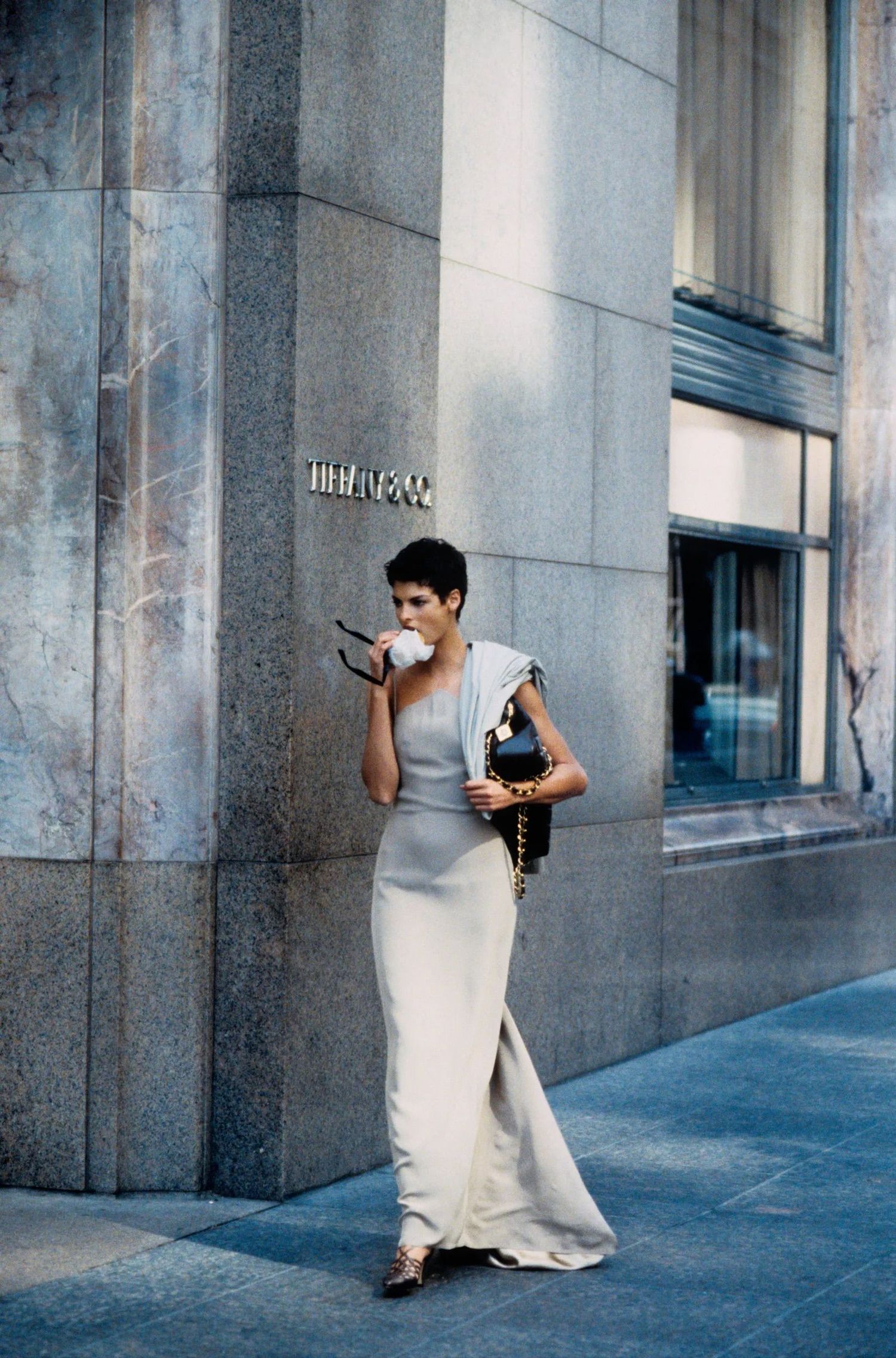

Christina Kruse and Savion Glover dance in the street with Kiara Kabukuru, center, who wears Armani’s fitted coat. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, August 1996

Between 1990 and 1995 the company grew rapidly, but Armani felt the burden of success. He later said of the period: “I could no longer take risks like I used to, and I couldn’t afford not to sell—I couldn’t even afford a drop in sales. My designing became a commercial responsibility.” More and more lines were introduced—in sleepwear, in beauty—and growth was maintained. Later in that decade Calvin Klein, Prada, a renewed Gucci, and the upstart Dolce & Gabbana would add to the crowd of rivals, led by Gianni Versace until his death in 1997.

By the 25th anniversary of his company and the 2001 retrospective at the Guggenheim, which reportedly drew 29,000 visitors a week, Armani was still immensely successful and powerful, yet no longer le dernier cri. During the early years of the second millennium he launched his hotel chain in partnership and assumed control of his manufacturing facilities to ensure vertical integration. Where he could not self-produce, he licensed, but only if he was ensured the last word (it was precisely this criterion that led to his exit from a highly profitable partnership with Luxottica).

He was, reputedly, approached several times with offers of investment from private equity groups and others keen to join the early boom of the conglomeration of luxury, but chose to keep the house he built his and his alone. He recounted once that three pitching investors had asked for a meeting with their banker. Armani said: “He was the most powerful man in Italian banking, and while the others spoke, he sat there, not saying a word. Then he looked over at the other men and said: ‘My dear sirs, Mr. Armani doesn’t need us. Let’s go.’ ”

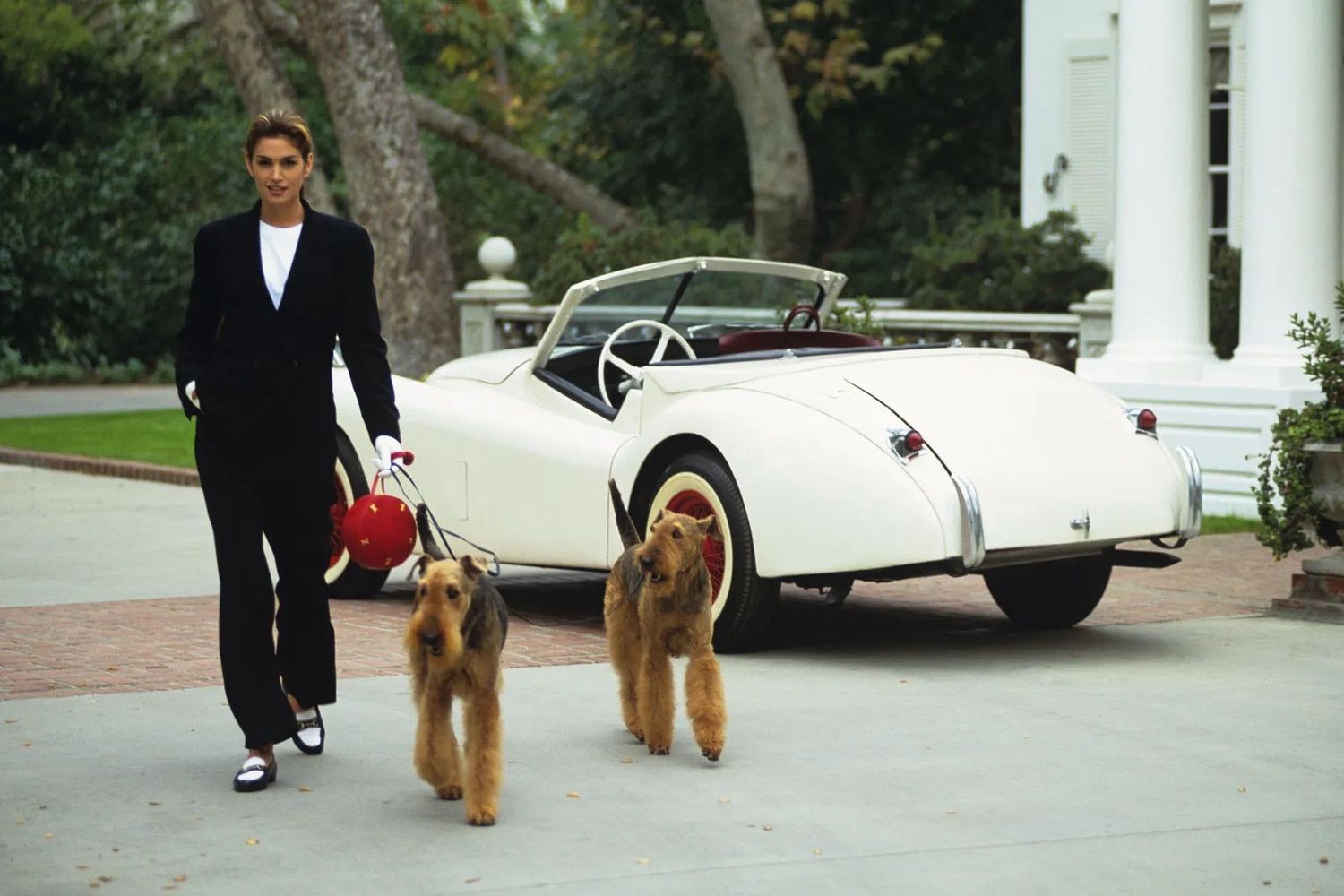

Cindy Crawford in a navy pantsuit by Giorgio Armani. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, March 1992

Armani remained a dedicated advertiser in the fashion press (the fateful 1976 call from Barneys came after it saw his first campaign in L’Uomo Vogue), but increasingly his collections were truer to himself than the times. And such was the power of his name that he had transcended the limits of that press and even the fashion system in general. As Franca Sozzani, the late editor-in-chief of Italian Vogue, once noted: “Like all the truly great designers in fashion history, Giorgio Armani is about style, not fashion. They find their style, and they stick to it, and that’s what he has done.”

In manner, Armani was reputedly sometimes reserved or prickly. During the regular post-show press conferences for the Italian press he would on occasion lob a rhetorical grenade in the direction of Prada or Dolce & Gabbana to the general merriment of all (Prada and Dolce & Gabbana apart). He often explained his bearing as shy. Despite that, the Armani aspect was formidable and his personal aesthetic ascetic. He was dedicated to personal fitness.

Nadja Auermann in an Emporio Armani coat in a neo-Victorian style. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, November 1993

Part of the designer’s apparent severity, and most certainly his seriousness and overall sobriety (although he confessed to taking LSD once and getting drunk a single time in his life), was likely the result of a childhood spent in straitened circumstances. He was raised in the town of Piacenza, close to Milan, in the 1930s and 1940s. His mother Mariù—after whom his beloved yacht was named—was a formidable matriarch charged with protecting Armani, his sister Rosanna and brother Sergio, through Allied bombing raids. Their father, Ugo, an accountant of Armenian lineage, found work hard to come by after the war. One of young Giorgio’s friends was killed by an explosion—a landmine, or gunpowder—on a Piacenza bomb site that left him badly scarred and in need of a 40-day hospital stay. This inspired him to pursue an initial ambition to be a doctor before he did military service and eventually found himself in Milan, the city that would make him and to which he would contribute so much.

Armani worked to the last, and even in his final collections would check every single look before ushering his models out onto the runway of the theater created for him by the esteemed Japanese architect Tadao Ando.

His mantra, he once observed, was that “perfectionism, and the need to always have new goals and achieve them, is a state of mind that brings profound meaning to life.”

The company statement said, funeral arrangements have been set at the Teatro Armani in Milan from Saturday, September 6 to Sunday, September 7, and will be open from 9 am to 6 pm.

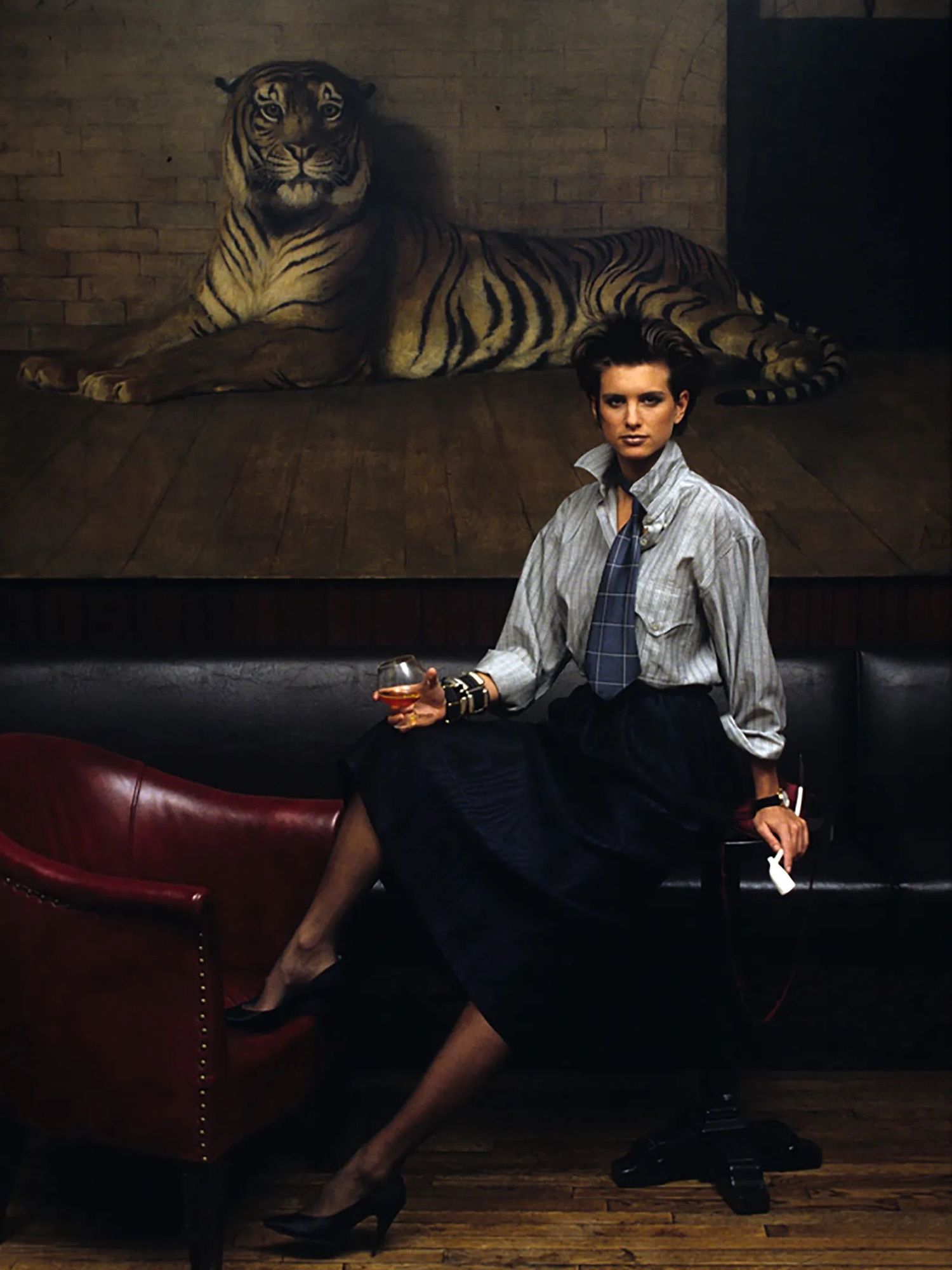

Lise Brand wears a skirt and blouse by Giorgio Armani. Photo: Oliviero Toscani, Vogue, March 1984

Photo: Peter Lindbergh, Vogue, December 1987

Jennifer Rubin in Giorgio Armani Couture’s silver-embroidered silk organza camisole and ball skirt. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, January 1989

Nadège du Bospertus keeps tune in Giorgio Armani’s “playful dress-up of … [a] chalk-striped pantsuit, done in paillette-studded silk chiffon.”. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, August 1992

Christy Turlington-Burns in Giorgio Armani’s dressed down pin-striped suit of silk. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, August 1993

“Giorgio Armani’s pared-down approach to the suit includes loosely cut trousers and a jacket that’s as relaxed as as shirt.”. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, January 1994

Nadja Auermann in Giorgio Armani's intricately worked shorts. Photo: Irving Penn, Vogue, March 1995

“Giorgio Armani knows how to make a dress that makes an entrance—by adding beads from top to hem.”. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, June 1988

Stella Tennant wears Giorgio Armani’s floral-print silk dress. Photo: Arthur Elgort, Vogue, November 2001

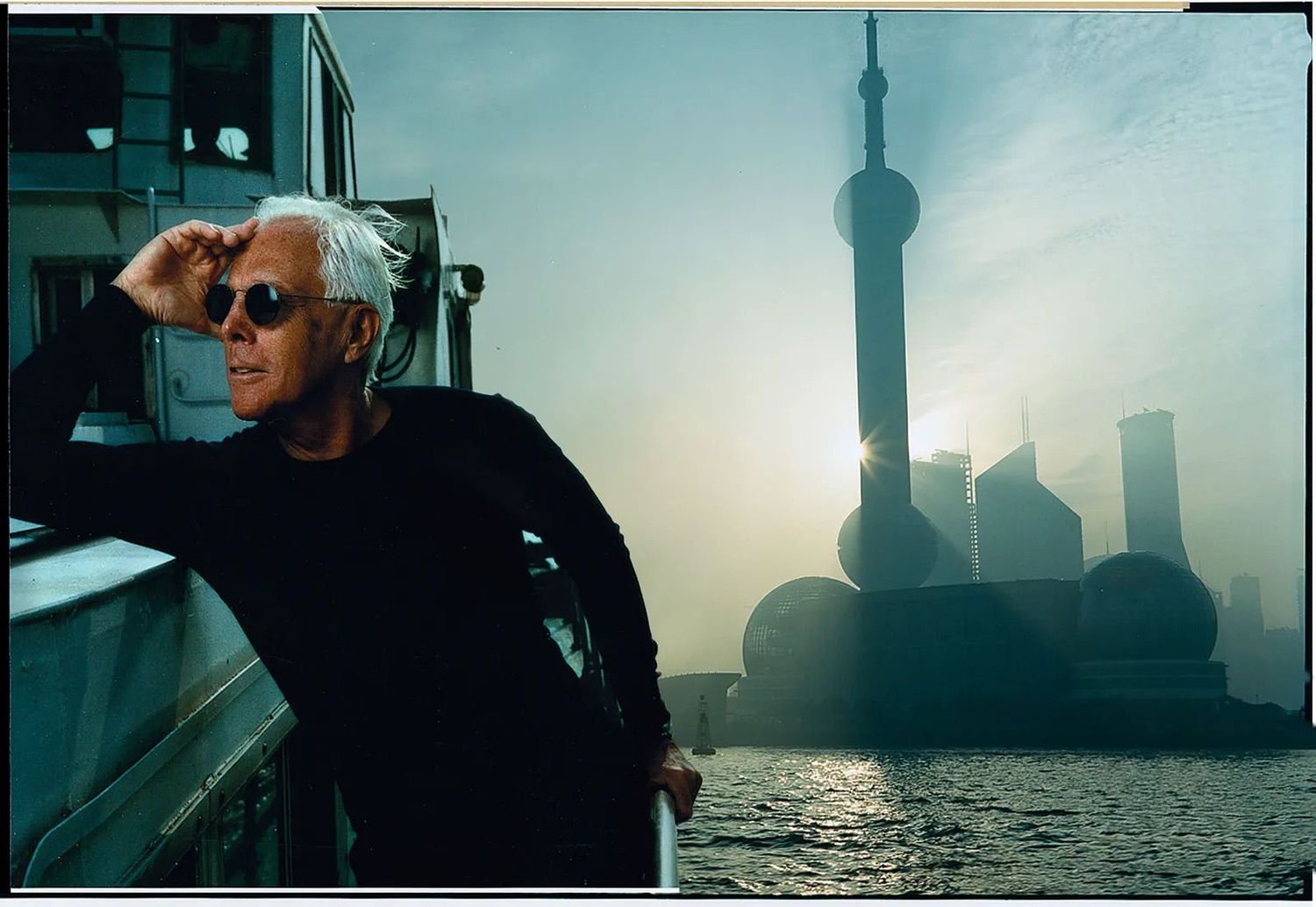

Giorgio Armnai’s “aerodynamic satin dresses” seen against the skyline of Shanghai. Photo: Norman Jean Roy, Vogue, September 2004

Giorgio Armani. Photo: Norman Jean Roy, Vogue, September 2004

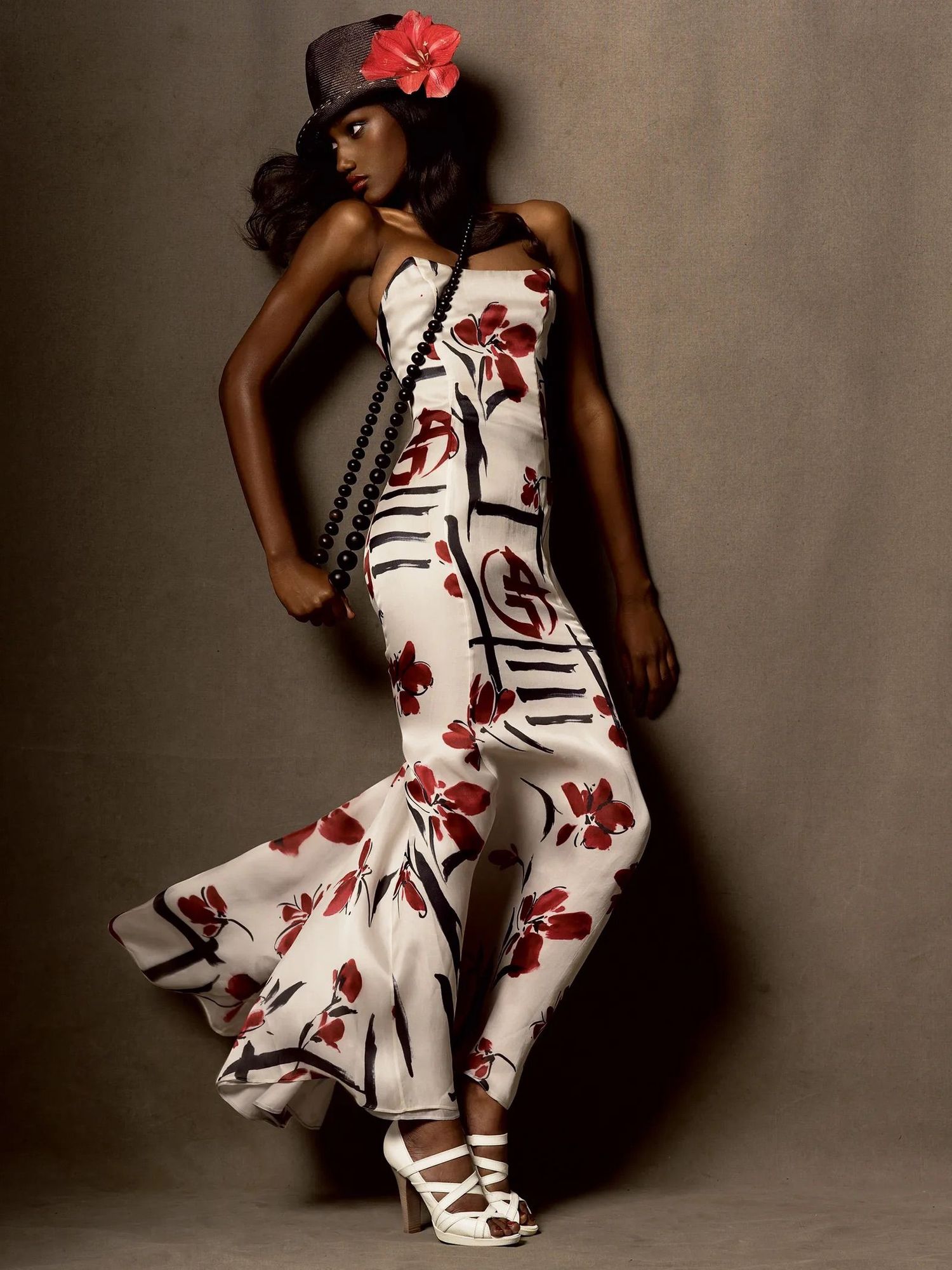

Jaunel McKenzie in Giorgio Armani’s calligraphy dress. Photo: Steven Meisel, Vogue, April 2005

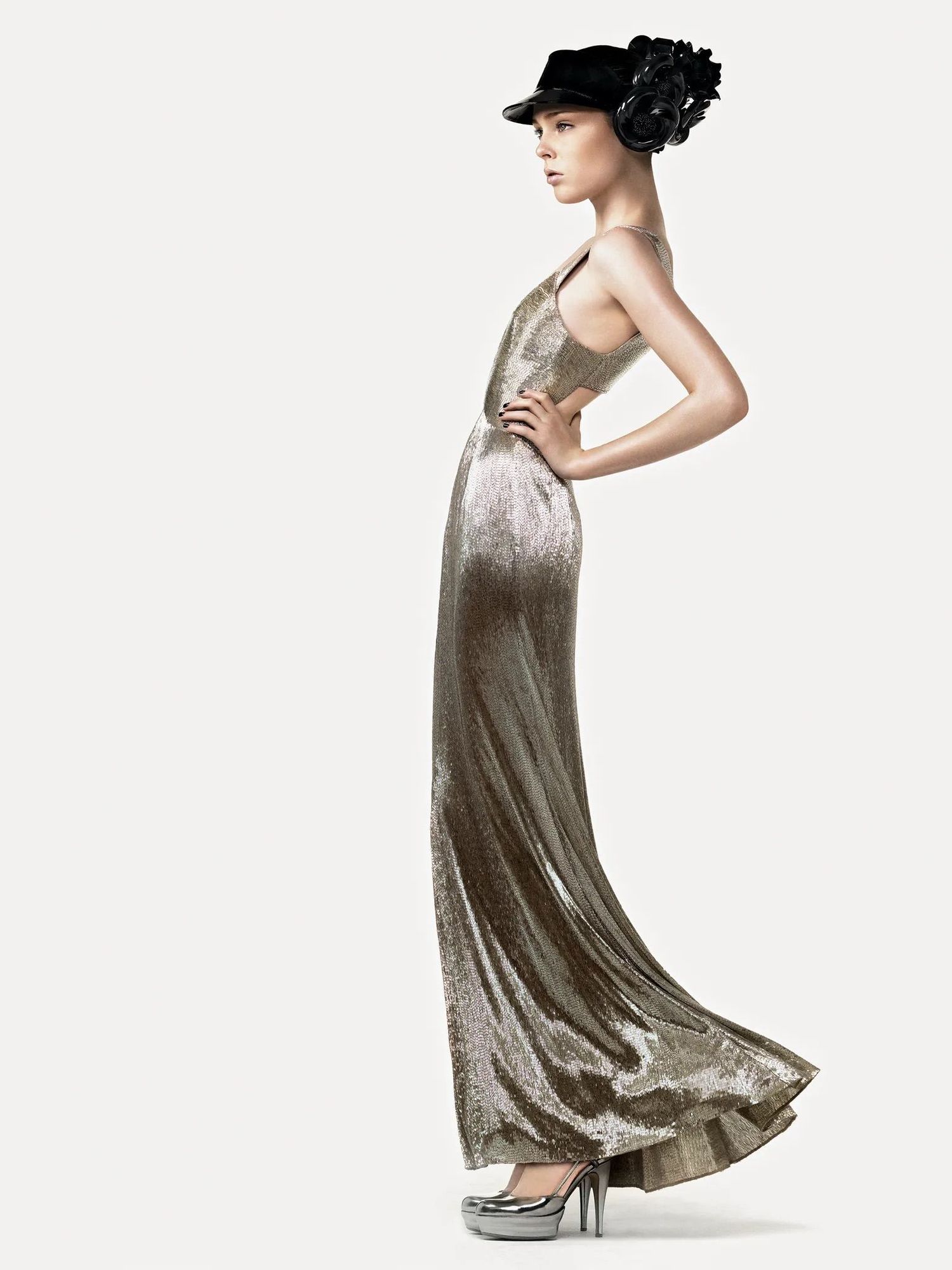

Coco Rocha channels retro-Hollywood glamour in Giorgio Armani’s platinum beaded gown. Photo: David Sims, Vogue, March 2007

Isabeli Fontana in Giorgio Armani’s “light-as-air” dress of silk layers. Photo: David Sims, Vogue, March 2009

Kristen McMenamy, dressed to thrill in Giorgio Armani’s wool suit and silk shirt. Photo: David Sims, Vogue, August 2010

Photo: Peter Lindbergh, Vogue, October 2010

Edie Campbell in a pale-pink silk organza Armani Privé dress with a crinoline lace skirt and airy-embellishments. Photo: David Sims, Vogue, September 2013

Cate Blanchett, an Armani loyalist, in a silk dress with lace and tulle appliqué from Armani Privé. Photo: Craig McDean, Vogue, January 2014

Raquel Zimmermann in Emporio Armani’s scarlet coat. Photo: Mikael Jansson, Vogue, September 2015

Yasmin Wijnaldum wears an Emporio Armani coat. Photo: Daniel Jackson, Vogue, September

Giorgio Armani. Photo: Annie Leibovitz, Vogue, May 2021

Photo: Micaiah Carter, Vogue, May 2021

Sora Choi wears a Giorgio Armani jacket. Photo: Samuel Rock, Vogue, August 2022

Bella Hadid wears a Giorgio Armani embroidered dress. Photo: Elizaveta Porodina, Vogue, August 2022

Originally published on Vogue.com