Next May's Met Gala looks to adopt an anatomical approach, with its exhibition honed around the omnipresence of the human body in high fashion

Fashion is coming out of the basement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Announced today, “Costume Art,” the spring 2026 exhibition at the Costume Institute, will mark the inauguration of the nearly 12,000-square-foot Condé M. Nast Galleries, adjacent to The Met’s Great Hall. “It’s a huge moment for the Costume Institute,” says curator in charge Andrew Bolton. “It will be transformative for our department, but I also think it’s going to be transformative to fashion more generally—the fact that an art museum like The Met is actually giving a central location to fashion.”

To mark the momentous occasion, Bolton has conceived an exhibition that addresses “the centrality of the dressed body in the museum’s vast collection,” by pairing paintings, sculptures, and other objects spanning the 5,000 years of art represented in The Met, alongside historical and contemporary garments from the Costume Institute.

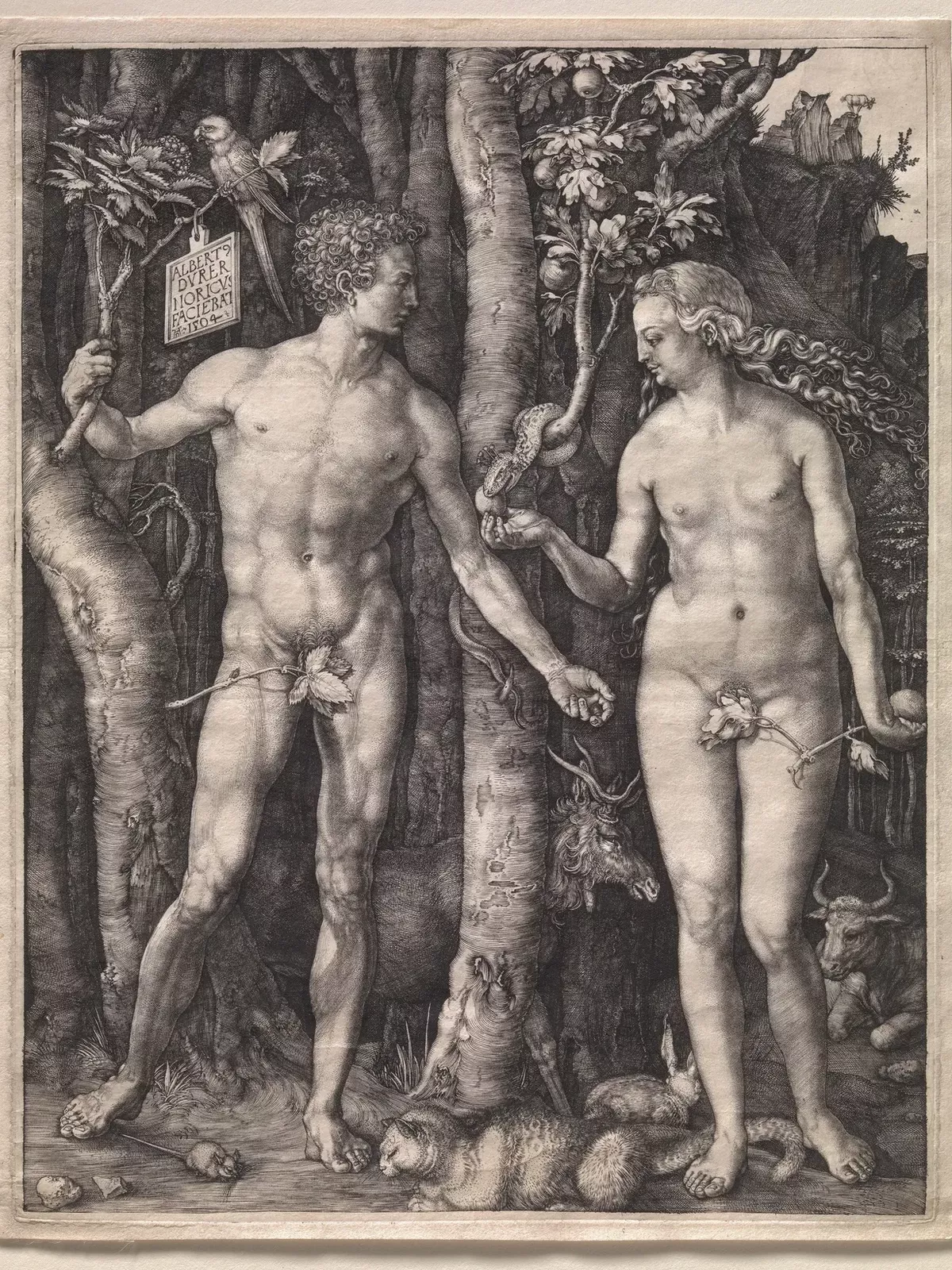

The Naked Body: Adam and Eve, Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471– 1528), 1504; Fletcher Fund, 1919 (19.73.1). Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

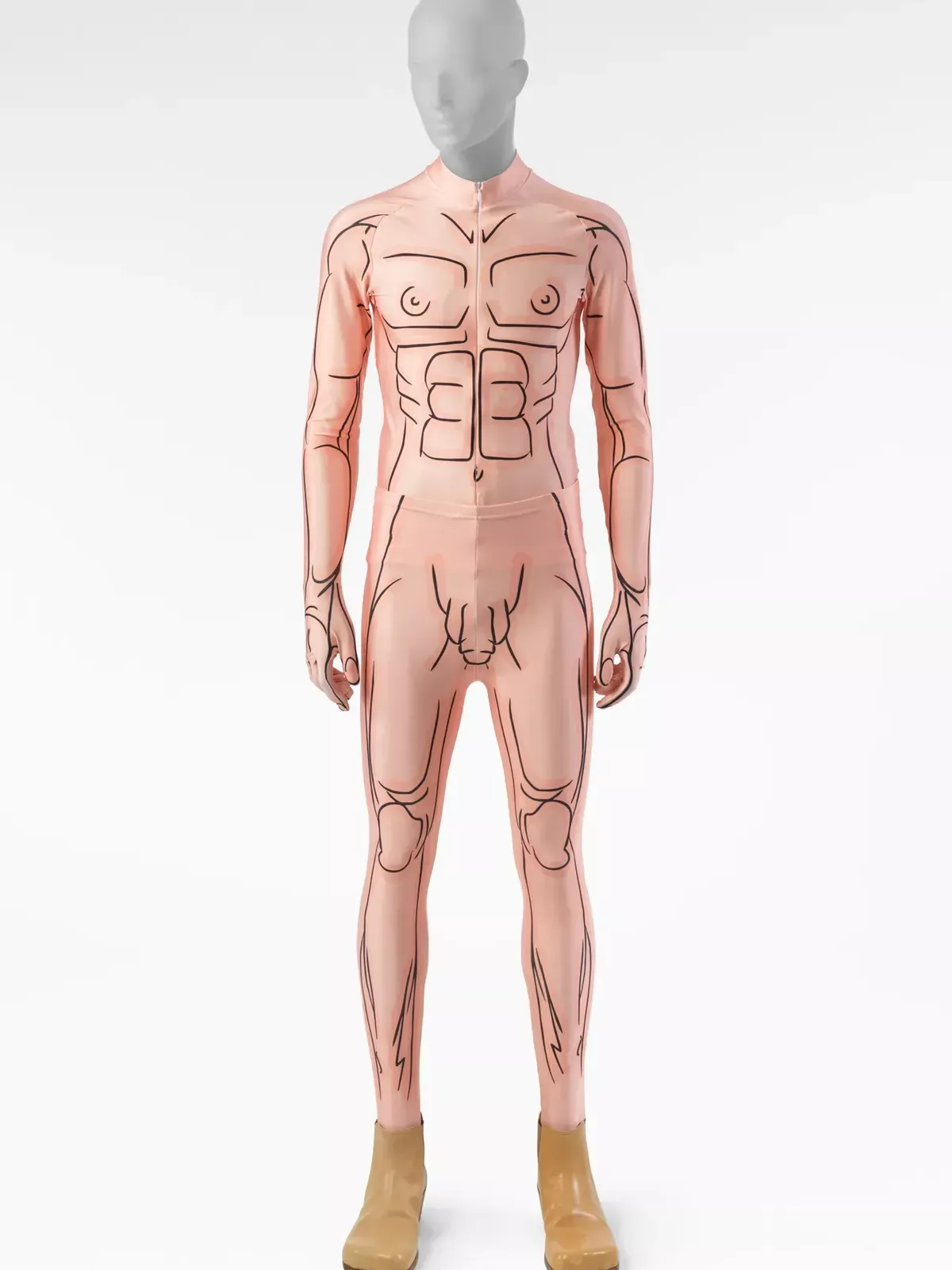

Ensemble, Walter Van Beirendonck (Belgian, born 1957), spring/summer 2009; Purchase, Friends of The Costume Institute Gifts, 2020 (2020.45a–d). Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

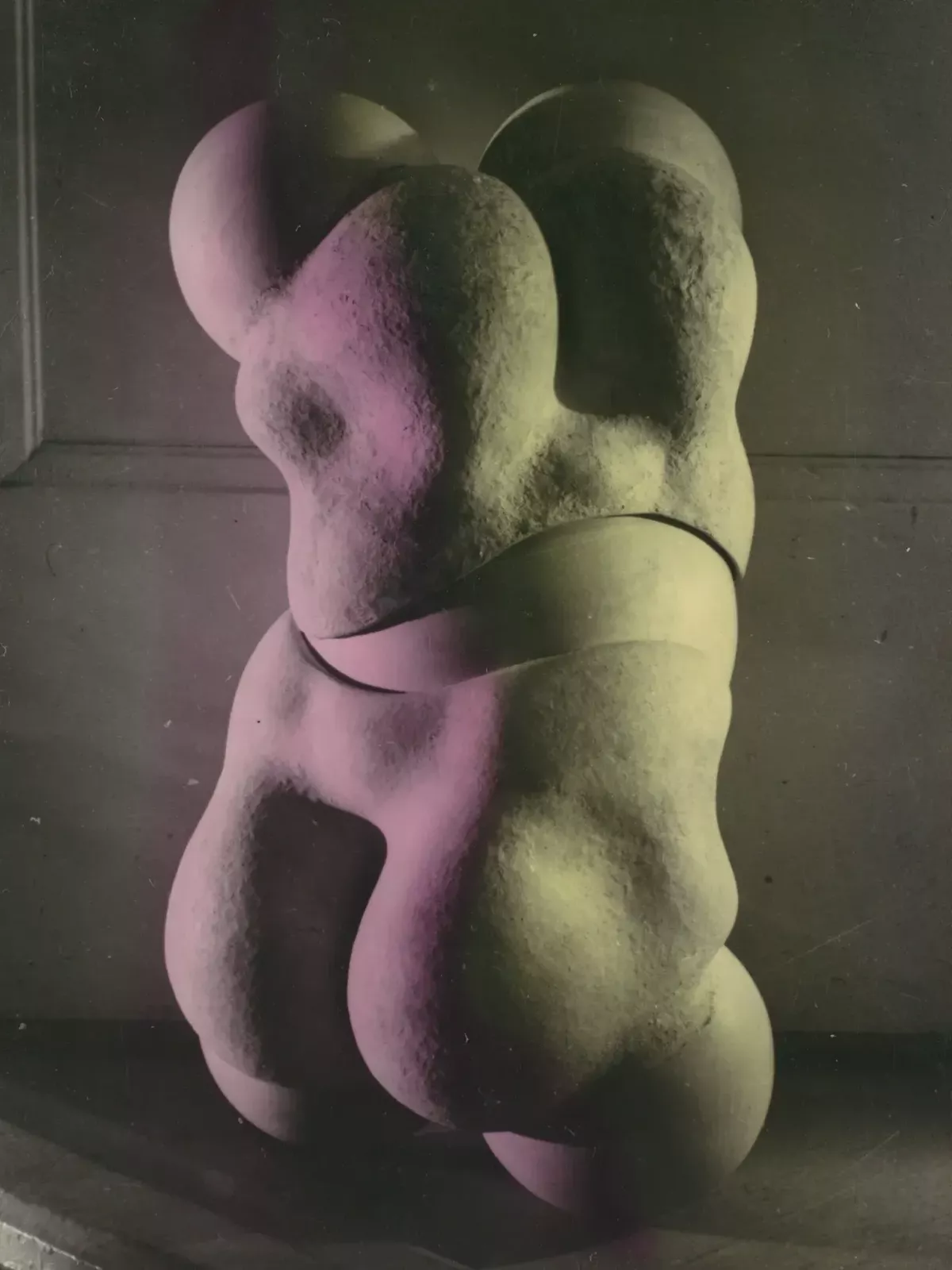

The Reclaimed Body: La Poupeé, Hans Bellmer (German, born Poland, 1902–1975), ca. 1936; Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell, 1987 (1987.1100.333). © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ensemble, Rei Kawakubo (Japanese, born 1942) for Comme des Garçons (Japanese, founded 1969), fall/winter 2017–18; Purchase, Funds from various donors, by exchange, 2018 (2018.23a). Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“What connects every curatorial department and what connects every single gallery in the museum is fashion, or the dressed body,” Bolton says. “It’s the common thread throughout the whole museum, which is really what the initial idea for the exhibition was, this epiphany: I know that we’ve often been seen as the stepchild, but, in fact, the dressed body is front and centre in every gallery you come across. Even the nude is never naked,” he continues. “It’s always inscribed with cultural values and ideas.”

The art and fashion divide stubbornly persists despite Costume Institute exhibitions like “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination,” which was the most-visited exhibition in The Met’s history with 1.66 million visitors. Bolton figures that the hierarchy endures precisely because of clothing’s connection to the body. “Fashion’s acceptance as an art form has really occurred on art’s terms,” he explains. “It’s premised on the negation, on the renunciation, of the body, and on the [fact that] aesthetics are about disembodied and disinterested contemplation.”

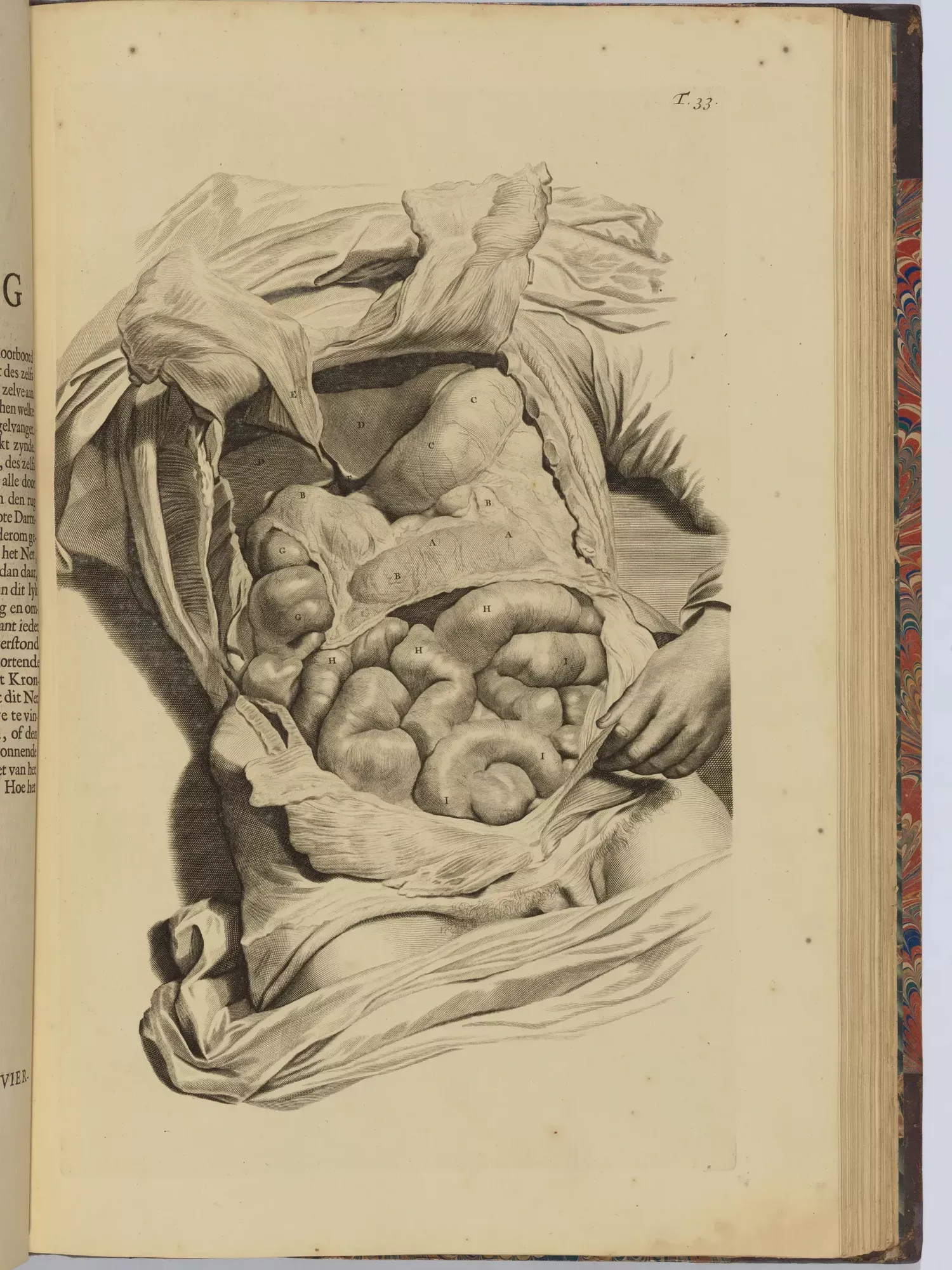

The Anatomical Body: Plate 33 in Govard Bidloo, Ontleading des menschlyken Lichaems, Abraham Blooteling (Dutch, 1640–1690) and Pieter van Gunst (Dutch, 1659–1724) After Gerard de Lairesse (Dutch, 1641–1711), 1728; Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1952 (52.546.5). Photo: Mark Morosse © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

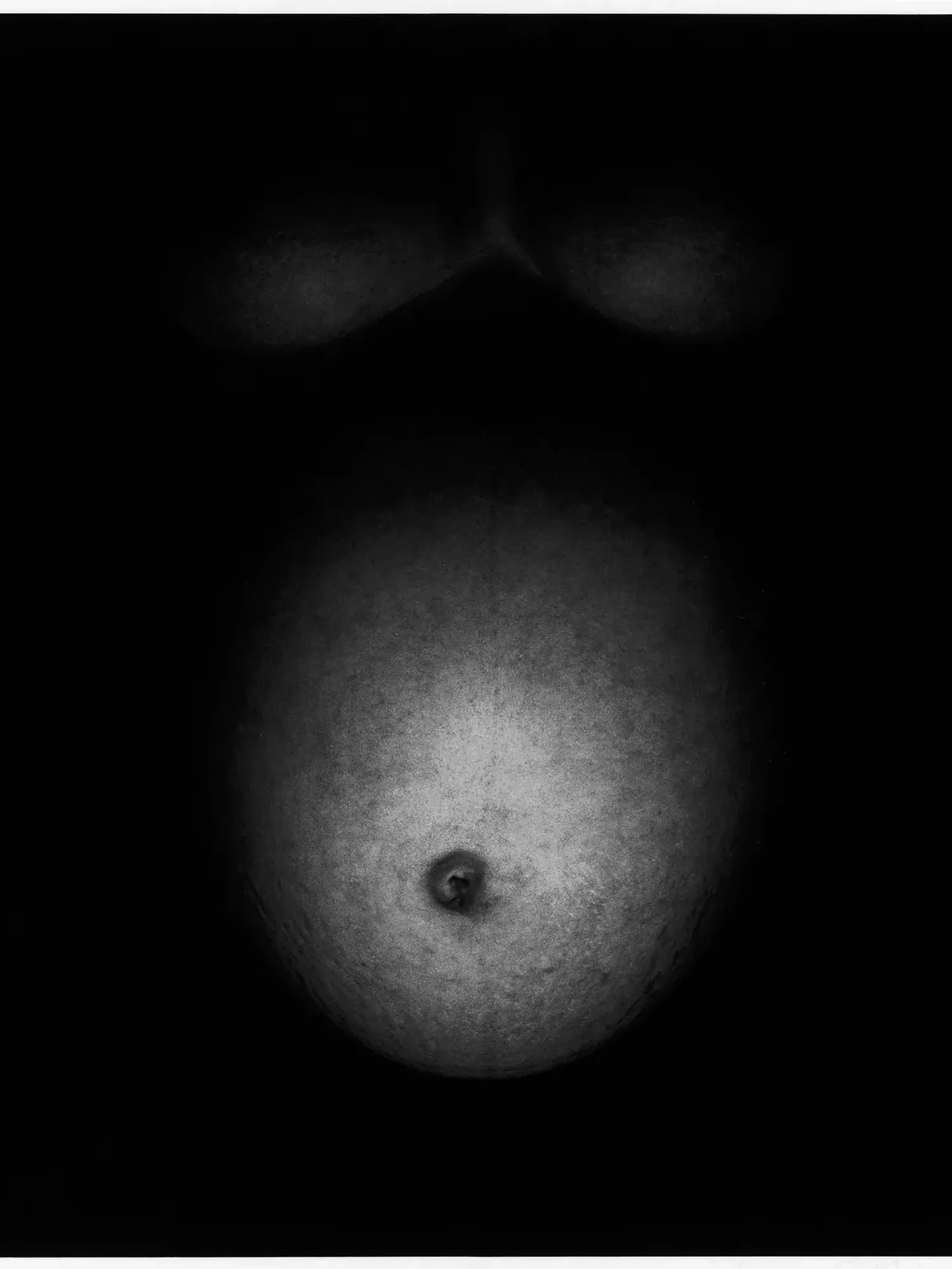

The Pregnant Body: Eleanor, Harry Callahan (American, 1912–1999), 1949; Gift of Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1991 (1991.1304). © The Estate of Harry Callahan; Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York. Photo: courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Pregnancy” dress, Georgina Godley (British, born 1955), fall/winter 1986–87, edition 2025; Purchase, Anthony Gould Fund, 2025. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Traditionally, Bolton admits, Costume Institute shows have emphasised clothing’s visual appeal, with the mannequins disappearing behind or underneath garments. His bold idea for “Costume Art” is to insist on the significance of the body, or “the indivisible connection between our bodies and the clothes we wear.” Fashion, he insists, actually “has an edge on art because it is about one’s lived, embodied experience.”

He’s organised the exhibition around a series of thematic body types loosely divided into three categories. These include bodies omnipresent in art, like the classical body and the nude body; other kinds of bodies that are more often overlooked, like aging bodies and pregnant bodies; and still more that are universal, like the anatomical body. Bolton’s is a much more expansive view of the corporeal than the fashion industry itself often promotes, with its rail-thin models and narrow size ranges. “The idea was to put the body back into discussions about art and fashion, and to embrace the body, not to take it away as a way of elevating fashion to an art form,” he explains.

The Classical Body: Terracotta statuette of Nike, the personification of victory, Greek, late 5th century BCE; Rogers Fund, 1907 (07.286.23). Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Delphos” gown, Adèle Henriette Elisabeth Nigrin Fortuny (French, 1877–1965) and Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo (Spanish, 1871–1949) for Fortuny (Italian, founded 1906), 1920s; Gift of Estate of Lillian Gish, 1995 (1995.28.6a). Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Bustle” muslin, Charles James (American, born Great Britain, 1906–1978), 1947; Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of Millicent Huttlest. Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Abstract Body: Impression of Amélie de Montfort, Jean- Baptiste Carpeaux (French, 1827–1875), ca. 1867–69; Purchase, Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Gifts, 1989 (1989.289.2). Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Indeed, the exhibition has been designed, by Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich of the Brooklyn firm Peterson Rich Office, to privilege fashion. In the high ceiling room of the Condé M. Nast Galleries (there is also a low ceilinged room), clothing will be displayed on mannequins perched on 6-foot pedestals, onto which the artwork will be embedded. “When you walk in, your eye immediately goes up, you look at the fashions first,” Bolton says.

Even more powerfully, the artist Samar Hejazi has been commissioned to create mirrored heads for the show’s mannequins. “I’ve always wanted to try to bridge the gap between the viewer and the mannequin,” Bolton begins. With a “mannequin where the face is a mirror, you’re looking at yourself. Part of that is to reflect on the lived experience of the bodies you’re looking at, and also to reflect your own lived experience—to facilitate empathy and compassion.” Going a step further, the museum will also be casting real bodies to embody the clothes. “As you go through, [the exhibition] will challenge normative conventions and, in turn, offer more diverse displays of beauty.”

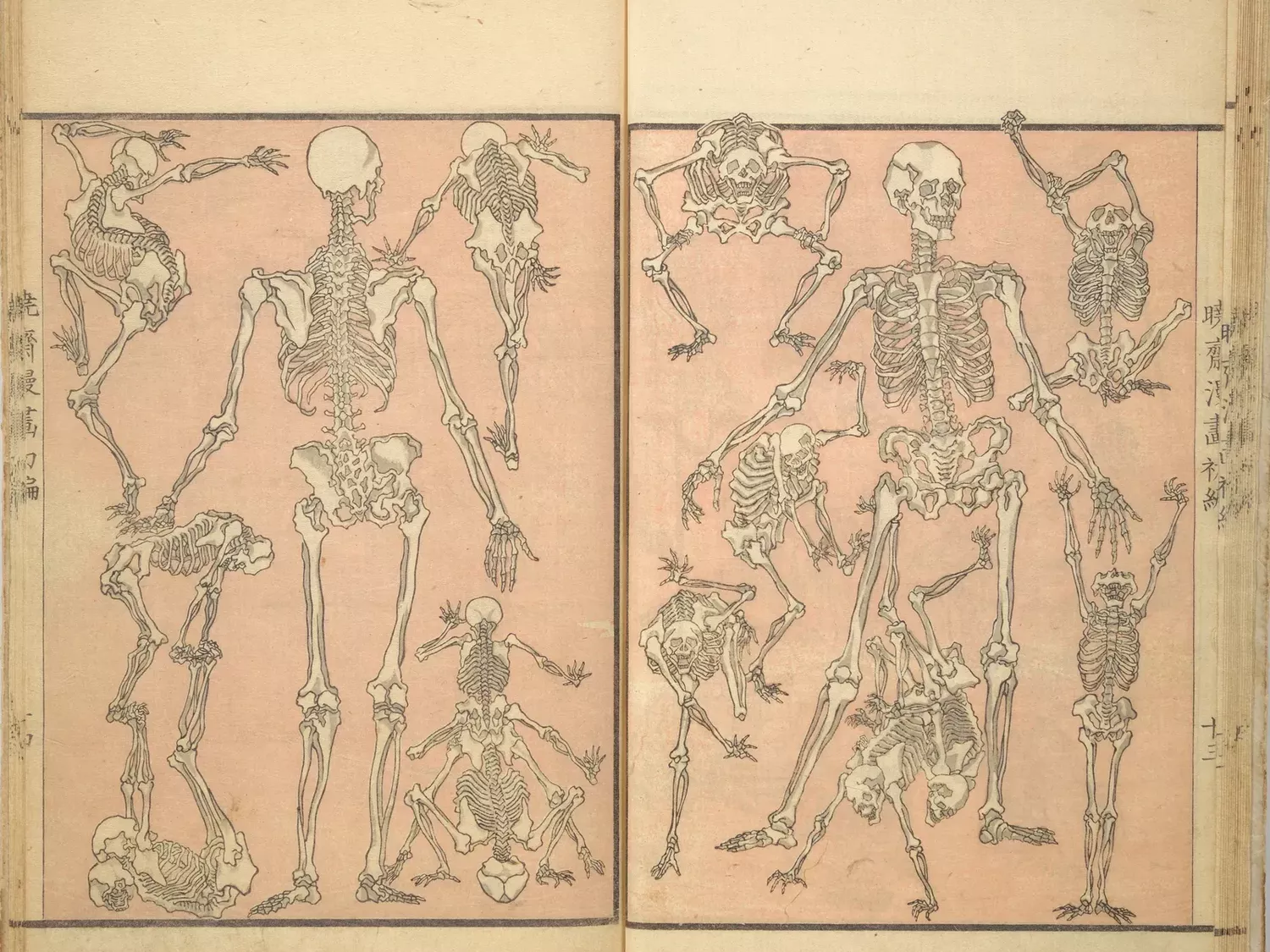

The Mortal Body: Kyōsai sketchbook (Kyōsai manga) 暁斎漫画, Kawanabe Kyōsai 河鍋暁斎 (Japanese, 1831–1889), Meiji period (1868–1912), 1881 (Meiji 14); Purchase, Mary and James G. Wallach Foundation Gift, 2013 (2013.765). Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Evening dress, Mon. Vignon (French, ca. 1850- 1910), 1875–78; Gift of Mary Pierrepont Beckwith, 1969 (C.I69.14.12a, b). Photo: Anna-Marie Kellen © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ensemble, Riccardo Tisci (Italian, born 1974) for House of Givenchy (French, founded 1952), fall/winter 2010–11, haute couture; Courtesy Givenchy. Photo: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

“Costume Art” is the first of Bolton’s exhibitions to be subtitle-less. The simplicity of the show’s name bolsters its objective: that fashion should most certainly be considered on the same plane as art. “I thought very, very carefully about that,” Bolton says. In fact, as recently as two weeks ago, the show did have a colon and a subtitle. “But then we took it out and it was like taking off a corset,” he laughs. “I thought, this is exactly what it should be. It’s bold, it’s strong, it’s a statement of intent.” The goal, he goes on, “is not to create a new hierarchy. It’s just to disband that hierarchy and to focus on equivalency—equivalency of artworks and equivalency of bodies.”

Made possible by Jeff and Lauren Bezos, with other funding from Saint Laurent and Condé Nast, “Costume Art” will run from May 10, 2026–January 10, 2027, following the Met Gala on May 4, 2026, which provides the Costume Institute with its primary source of funding for all activities.

This announcement was originally made on Vogue.com