The designer, who has passed away at the age of 76, was a key engineer of the signature silhouettes of the 1980s

Le Figaro has confirmed the death of Claude Montana, the French designer whose extreme silhouettes, anchored on a broad shoulder, defined the 1980s. The news comes in the middle of a season in which his work has been referenced by a new generation of fashion talents, who, like Alexander McQueen and Nicolas Ghesquière before them, are inspired not only by Montana’s work but also by the strength and decadence of a decade inhabited on catwalks and magazine pages by his Amazons.

Montana (known to friends as Clau-Clau) was born Claude Montamat in Paris in 1947 – the year Christian Dior introduced the postwar’s first extreme line, the New Look. His mother was German, his father Catalan and a former soldier. Like Paco Rabanne before him, Montana’s career started with jewellery. Having earned his degree, in 1964 Montana moved to London, where he reportedly met Olivier Echaudemaison, who was then styling British Vogue covers and used some of Montana’s jewellery. “Claude arrives looking like Little Lord Fauntleroy,” the makeup artist told Vanity Fair in 2013 of those early days. “He had curly blond hair and was wearing a velvet suit and a shirt with ruffles. He was nothing like the biker that he became.”

Returning to Paris, Montana started working with leather and for a time shared an apartment with Thierry Mugler. (The two would later form opposing fashion camps à la Lagerfeld and Saint Laurent before them.) Journalist Mary Russell introduced Montana, then working for Ferrer y Sentis, to Vogue readers in a 1977 story about rising talents in the fashion capital. Montana came up in the industry alongside the likes of Agnes B., Anne-Marie Beretta, Issey Miyake, and Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, who once asked Montana to walk in one of his shows. Per Russell: “Claude Montana’s life hasn’t changed in all the years he has been working. His fabrics are natural wools and silks and special tweeds that he has made up in Ireland. Leather is his big love, and his sense of color is extraordinary. He works out intricate hair and makeup for his shows, and all his friends come and help put the collection together…. His leathers are expensive, but even at high prices, they’re selling. He hopes someone will invest in one of his jackets, but has some very inexpensive T-shirts and beautiful wide silk shirts…. Again, the same story; he proposes clothes...the selection and mixing are up to the person who buys them. And, like his colleagues, he, too, lives simply, sees a few friends, loves music, dancing in New York and at Le Sept in Paris, and wouldn’t change his life for all the money in the world.”

Montana, spring 1995 ready-to-wear. Photo: Getty Images

Among the Frenchmen in the group, which would come to include Jean Paul Gaultier, Montana was arguably the least camp. He placed less emphasis on the theatrics of the show, though the behind-the-scenes drama, fueled by sex, drugs, and alcohol, would become seismic.

In 1979, with line, proportion, and gesture, Montana set the template for the greed decade when he opened his own ready-to-wear business. In June of that year, Vogue proclaimed his dramatic silhouette the “most-talked-about look in Paris – for the shape, the shoulders. The surprise: This look is done without heavy padding, without stiffness, it’s all in the fabric...the design.” In some ways Montana’s new look was the inverse of Dior’s, with the width at top, narrowing at the bottom, with a waist emphasis – but their starting points were worlds apart. Flowers and a soft femininity were not a lure for Montana, who, unlike the older Frenchman, was openly homosexual and whose tastes leaned more toward the hard-edged and transgressive aesthetic of Tom of Finland.

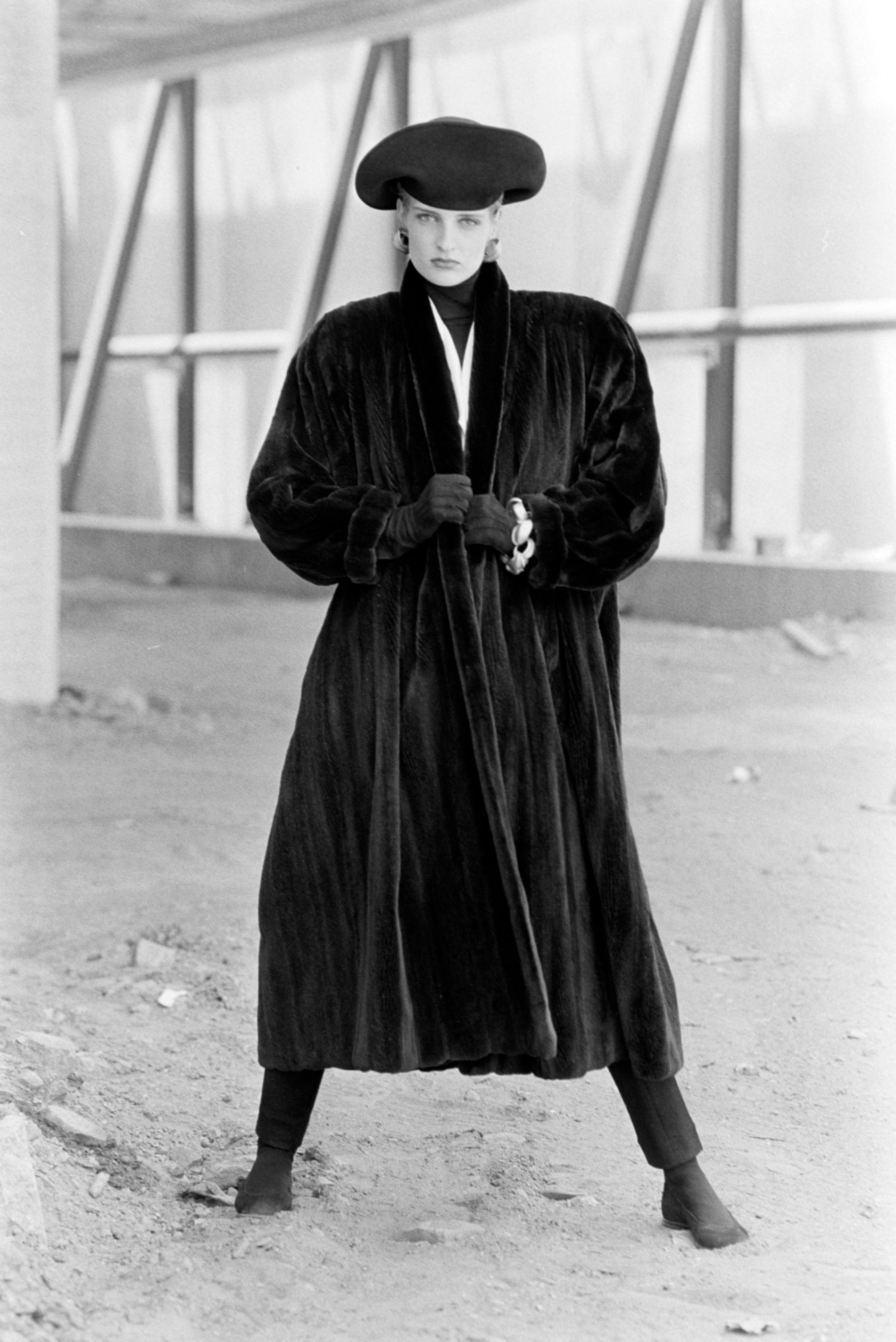

Claude Montana for Birger Christensen autumn '85. Photo: Getty Images

The late curator Richard Martin touched on this aspect of the designer’s work, writing: “Few designers have been as virulently attacked as Montana has, sometimes for ‘gay-clone’ proclivities to leather, for supposed misogyny, for impractical clothing, for excessive accoutrements. Leather jackets borrowed from menswear – bikers and the military – caused strong controversy in the American press and market in the 1980s when Montana appropriated them.” Launching menswear in 1981, Montana often applied haberdashery elements to his ready-to-wear, and the result was to imbue his designs with power. Detractors said the results were cartoonish, but the confidence and purity of his vision were undeniable and suggested other ways of existing in the world and/or dominating it.

Photo: Getty Images

Montana’s work wasn’t all about strictness and geometry, as Martin wrote; it was “based on circuiting spirals and a few strong lines realized on the body.” The designer often put those curves into orbit, as it were; there were certain sci-fi elements to his work. Vogue found an out-of-time element to his output. “While other designers are tossing a backward glance at a world of bygone fantasy – at bustles, bustiers, and tulle – one thoroughly modern designer stands out: Claude Montana,” noted the magazine in 1986. “Like a sharply focused laser beam, he continues his single-minded linear rush toward the future: toward one solid, strong, distinctive look; one unique signature style that comes through in everything – whether it is his sensuous gray jerseys, his luxurious furs, his hallmark leathers.” As the designer put it a year later: “Between very pared-down design and exaggerated design, there is a balance, which is the future.”

Montana’s rise was meteoric, but his fall was just as precipitous. In 1989 he was picked to be the successor to Marc Bohan at Dior, but he chose to go to Lanvin instead. Soon after things started to unravel; he was becoming elusive in inverse proportion to the extroversion of his work. In 1992 his contract with Lanvin ended; the following year Montana and his muse, the American expat model Wallis Franken, entered into a mariage blanc. Three years later she’d be found dead in the courtyard of their home, and by 1997 the business was bankrupt. Montana became, as Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni once put it, fashion’s Garbo; his influence pervasive, his person far removed from the maddening crowds that once clamored to see his shows.